# Libraries

library(ggplot2)

library(dplyr)

# Load the Titanic dataset

titanic <- read.csv("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/GeorgeOrfanos/Data-Sets

/refs/heads/main/titanic.csv")19 Data Visualization with ggplot2

19.1 Introduction

In this chapter, we introduce data visualizations in R using

ggplot2, the most widely used package for graphical

representation in R. This package is part of the

tidyverse collection, making it highly compatible

with tools like dplyr for data manipulation. To keep

things simple and focused, we’ll use the

Titanic dataset for all examples. This dataset is

available from several public sources, including GitHub and Kaggle.

The logic behind ggplot2 is modular: we begin with a

basic plot and then add layers of various elements to specify

additional components, such as points, lines, labels, or colors.

Just as we use the pipe operator (%>%) in

dplyr to build data workflows step by step,

ggplot2 follows a

layered grammar of graphics. This approach allows

us to define clearly and systematically what should appear in a

plot, making our code flexible, readable and auditable.

19.2 Preparing the Environment

Let’s begin by loading the necessary R packages,

dplyr and ggplot2, and importing the

Titanic dataset:

The Titanic dataset contains information on 891 passengers aboard the RMS Titanic. This version is a cleaned subset of the original passenger manifest and is commonly used for educational and modeling purposes.

Since we’ll analyze this dataset in the next chapter as well, here we will only briefly describe the three variables we’ll focus on:

-

Fare: The fare paid for the ticket

-

Age: The age of the passenger in years

-

Survived: Indicates whether the passenger survived (

1) or did not survive (0)

To simplify our plots, we will create a subset of the dataset that

includes only these three variables, while transforming the variable

Survived to a factor:

# Subset the dataset to keep only the three relevant columns

titanic_subset <- titanic %>%

select(Fare, Age, Survived) %>%

mutate(Survived = as.factor(Survived))19.3 Starting from Scratch

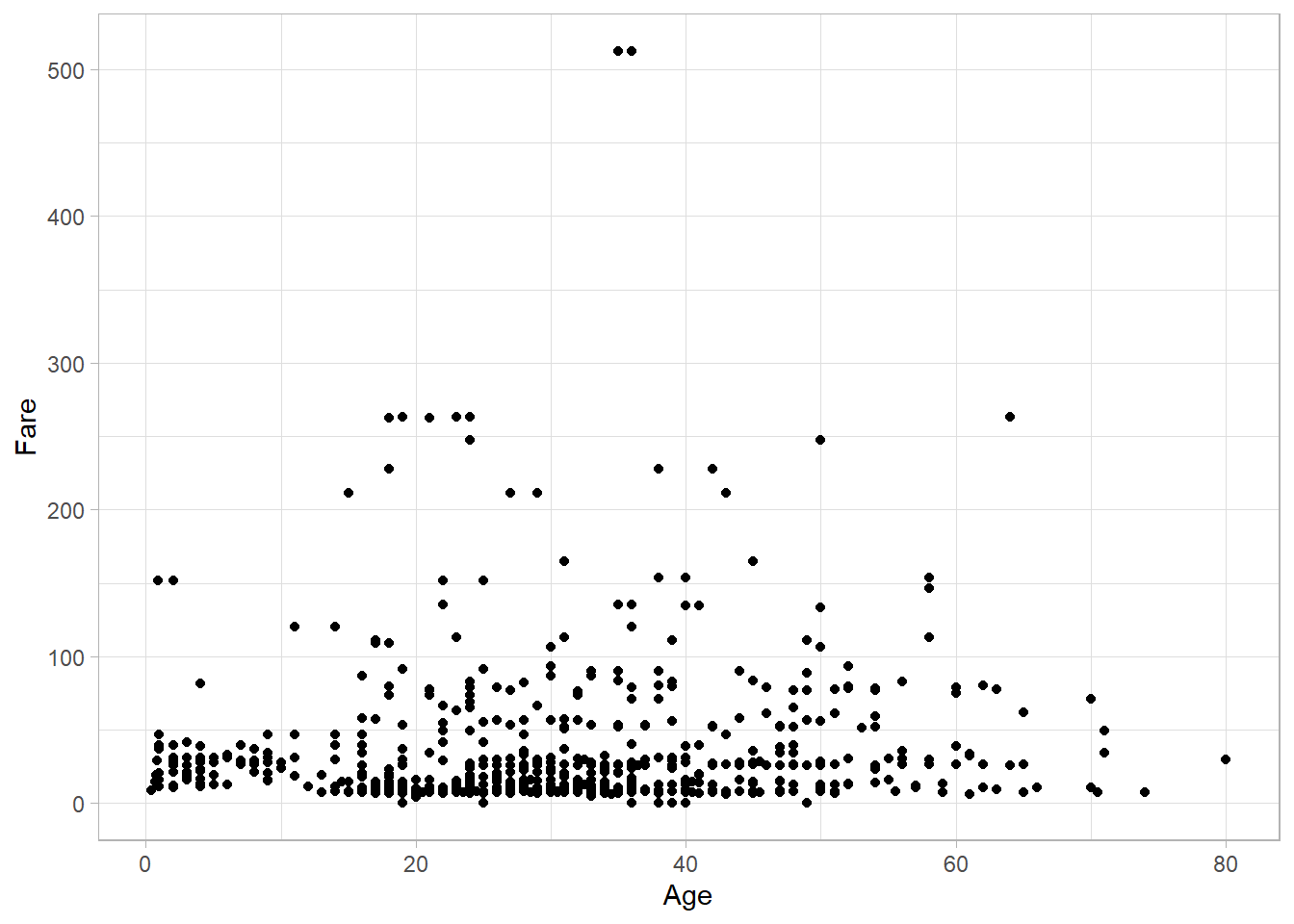

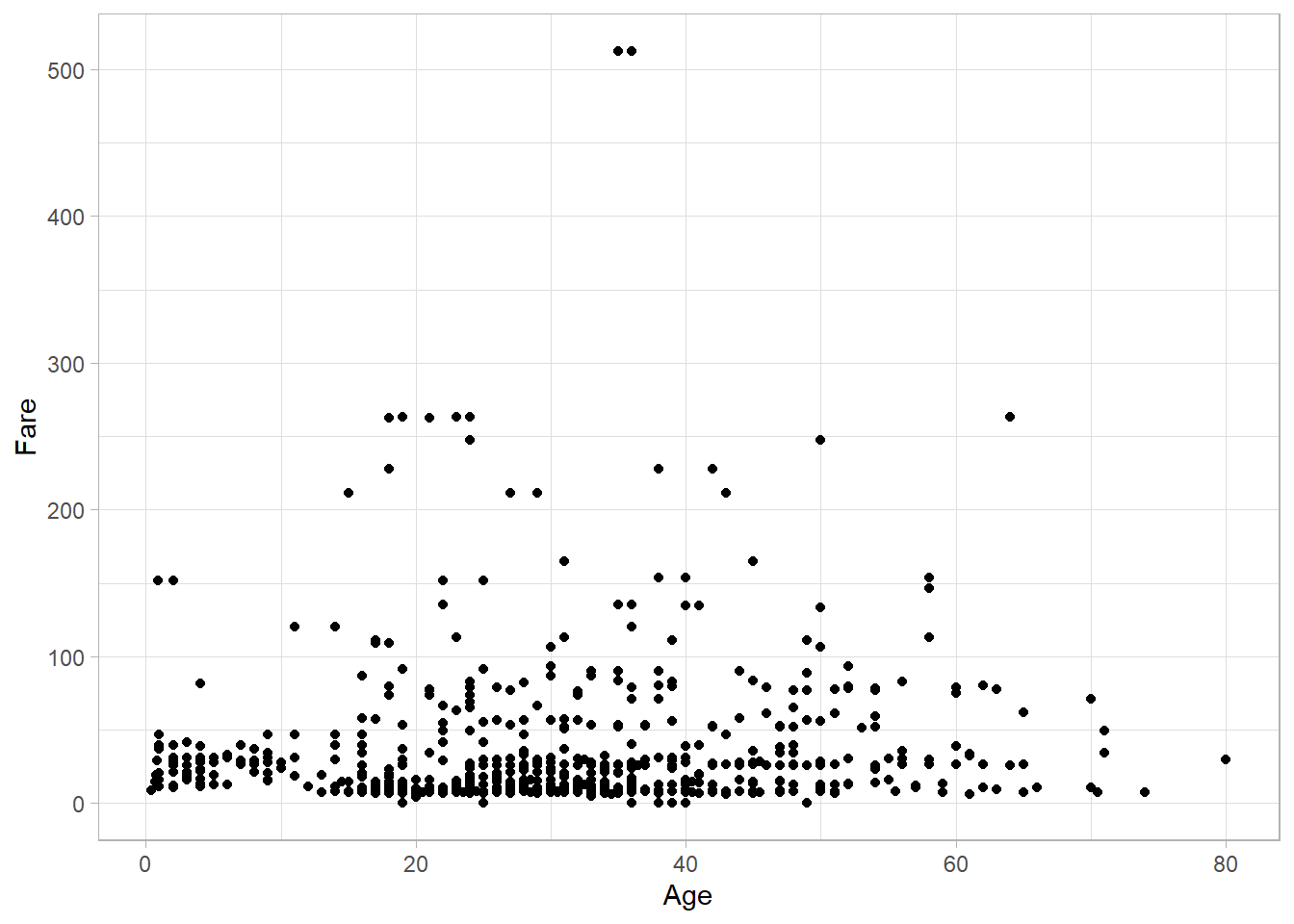

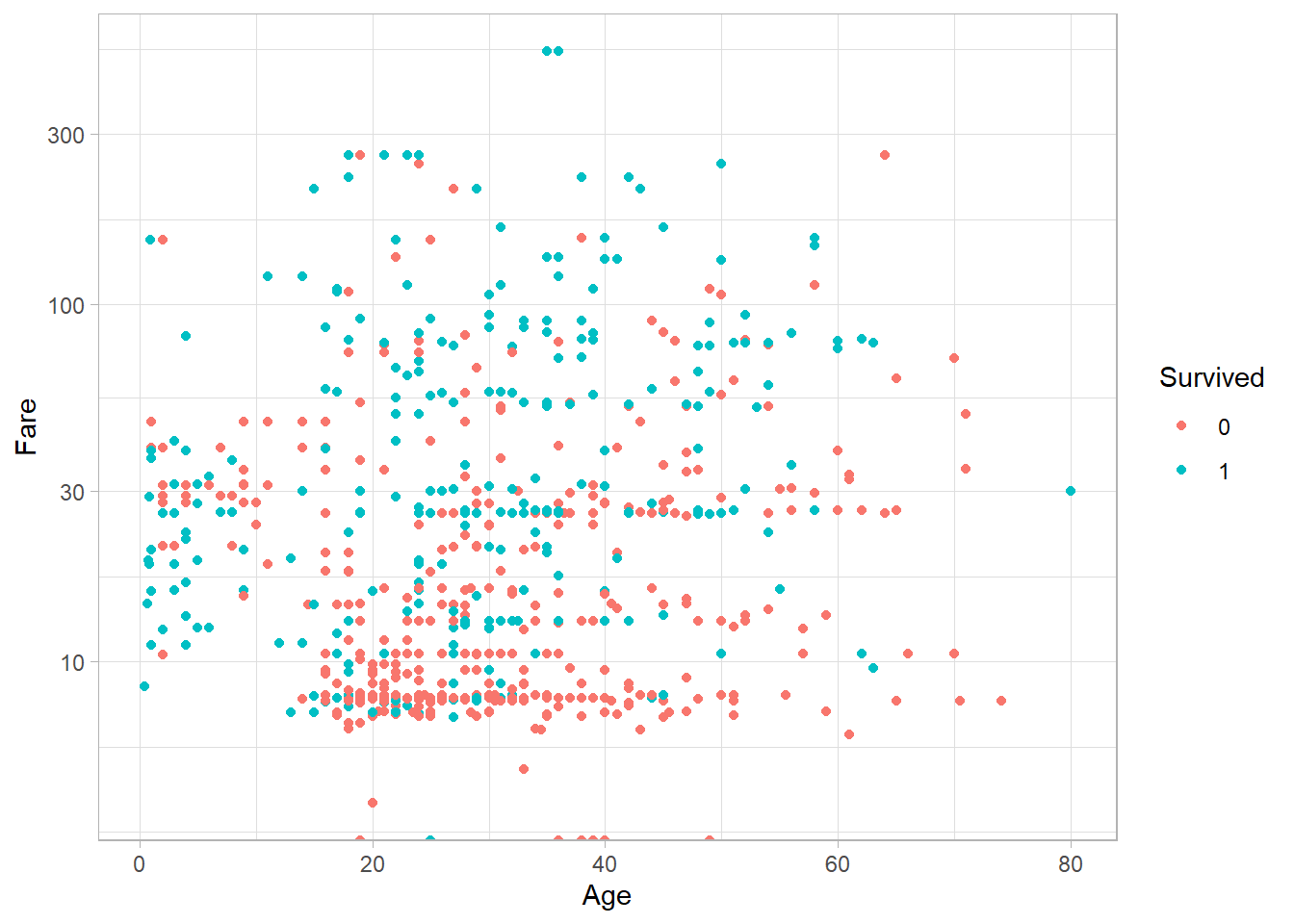

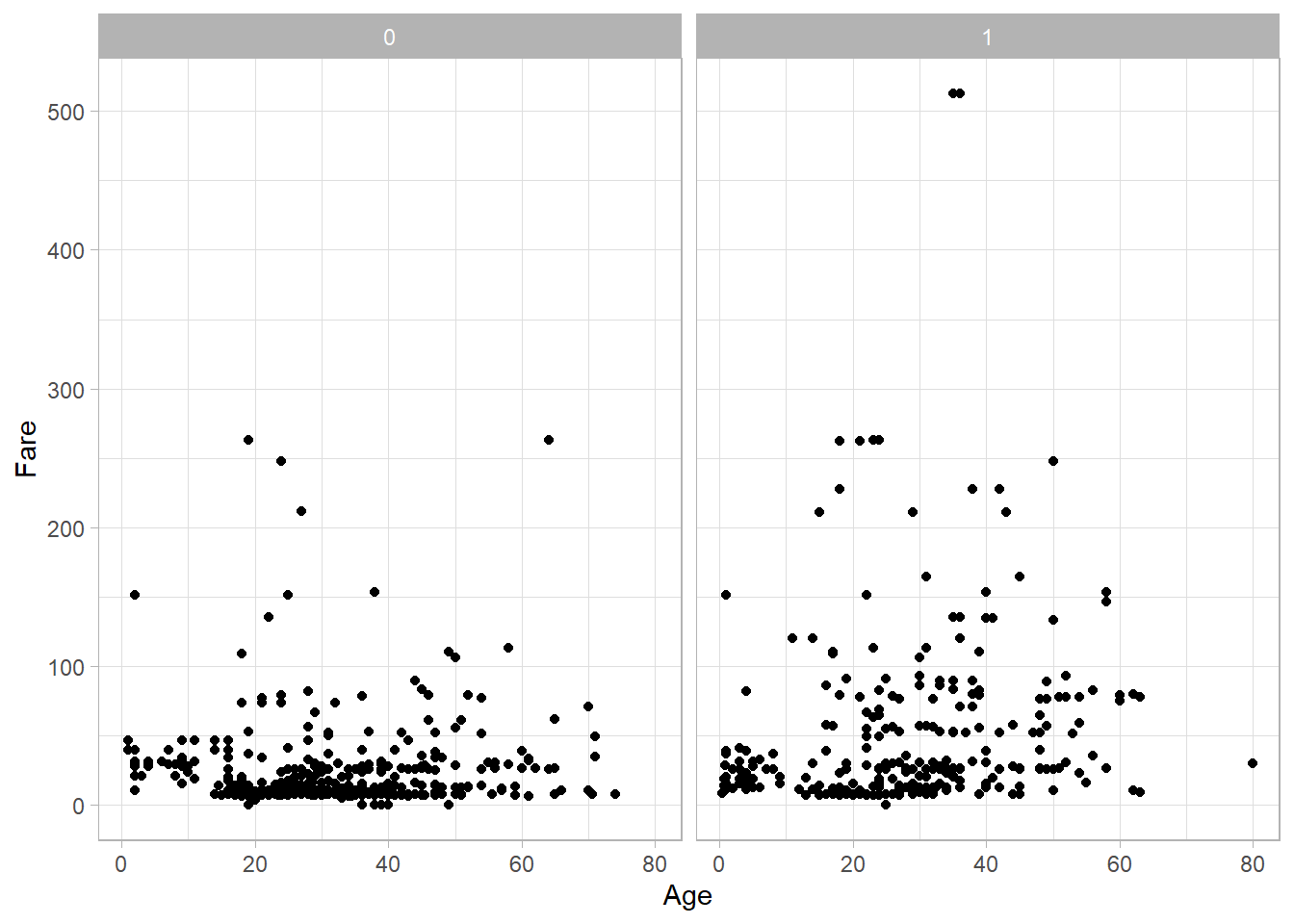

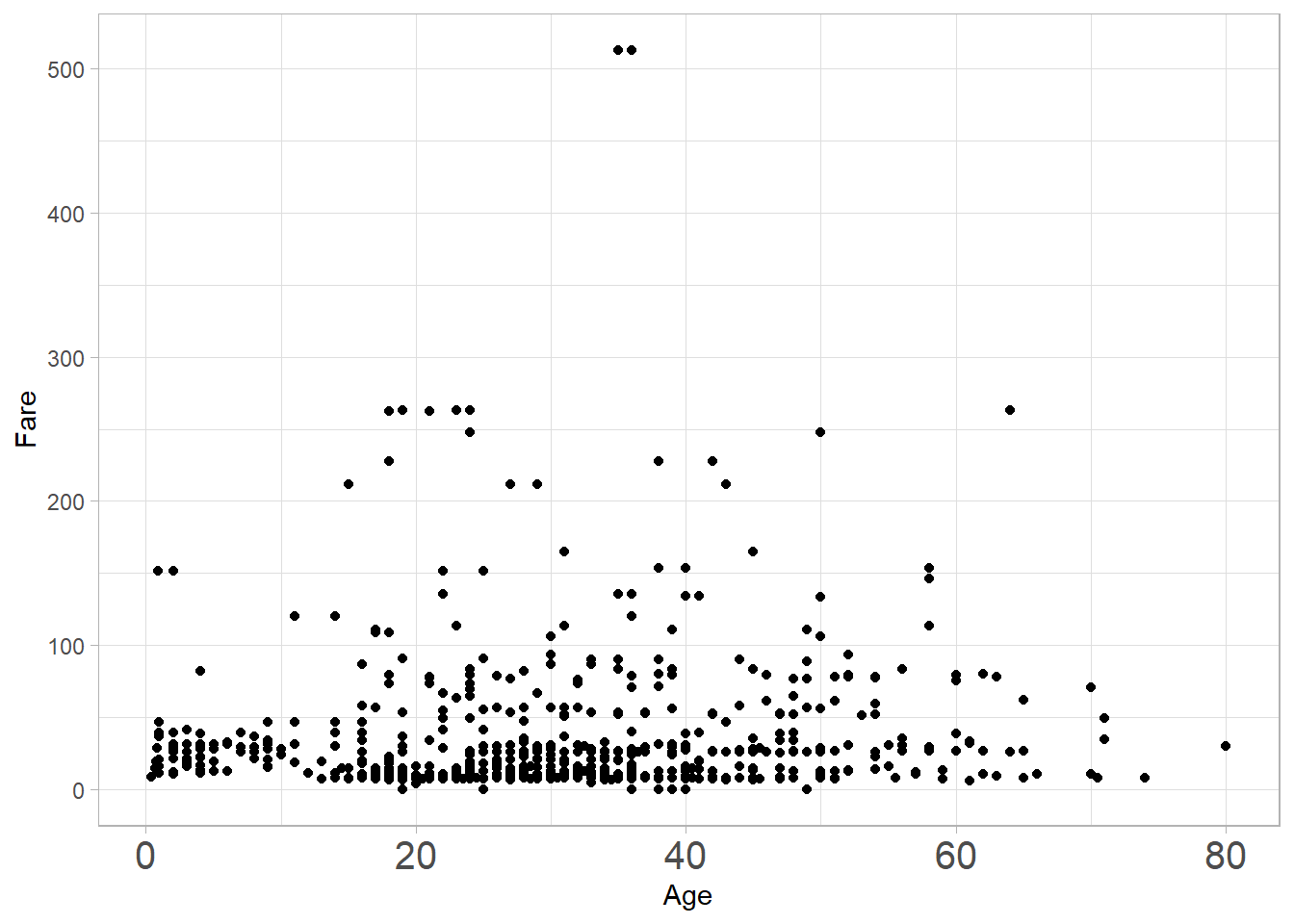

The plot below shows the relationship between Age and

Fare:

There is no strong association between these two variables—older

passengers could have either cheaper or more expensive tickets

compared to younger passengers. In statistical terms, there is no

clear correlation between Age and Fare.

Let’s now walk through on how to re-create this plot from scratch

using ggplot2.

Whenever we begin a new plot, we use the

ggplot() function. The first argument we need to

specify is the data we want to plot using the

data argument. For example, to start a plot based on

the titanic dataset:

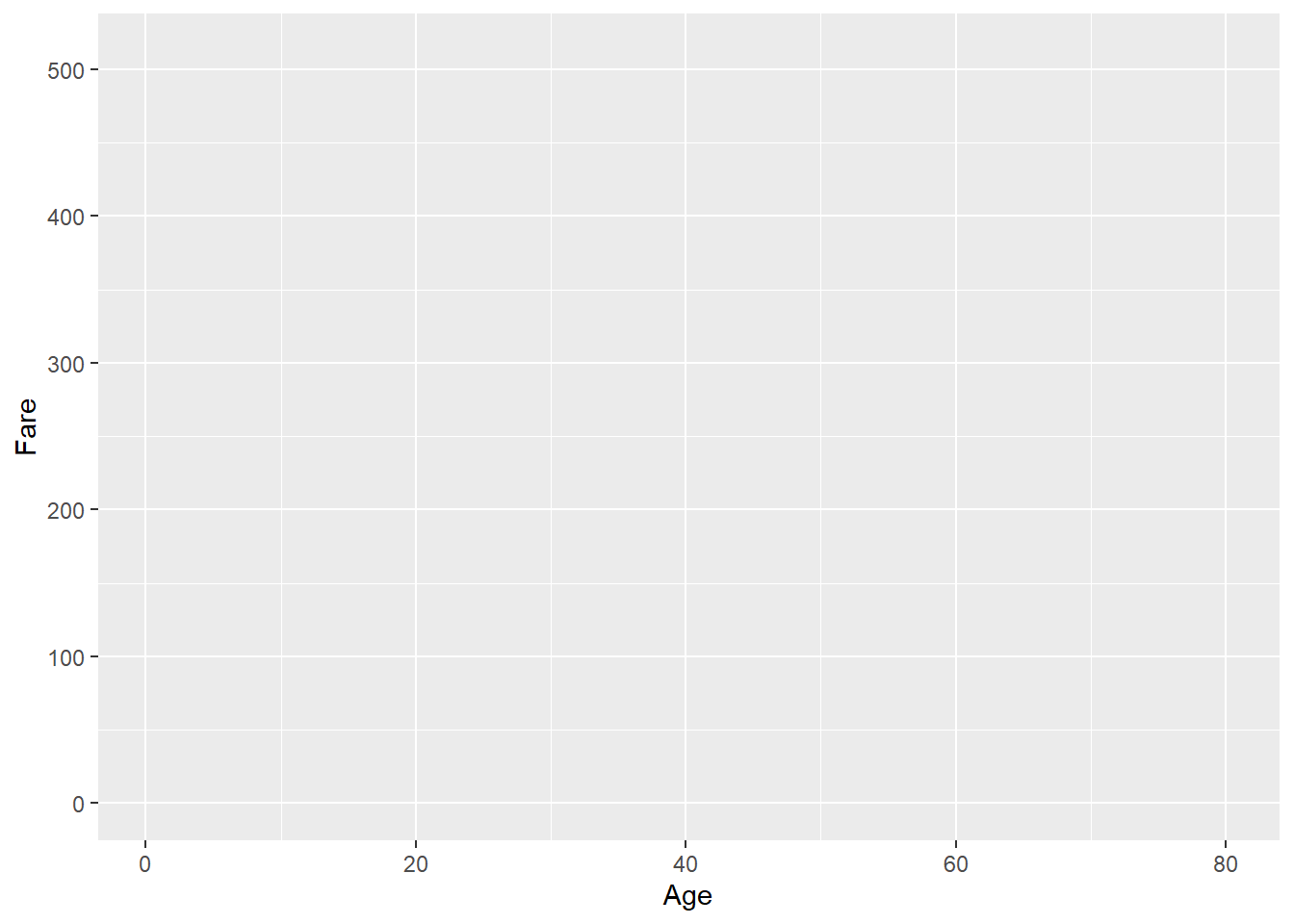

# Start a plot

ggplot(data = titanic_subset)

This generates an empty plot. Although it might seem like something is missing, this is actually expected; even though we have specified the dataset, we have not yet told R what we would like to plot (or how to plot it).

Next, we define the aesthetic mappings using the

aes() function, which stands for aesthetics. In

ggplot2, aesthetic mappings link variables in the

dataset to visual properties like position (x, y), color, size, etc.

To set Age on the x-axis and Fare on the

y-axis, we use:

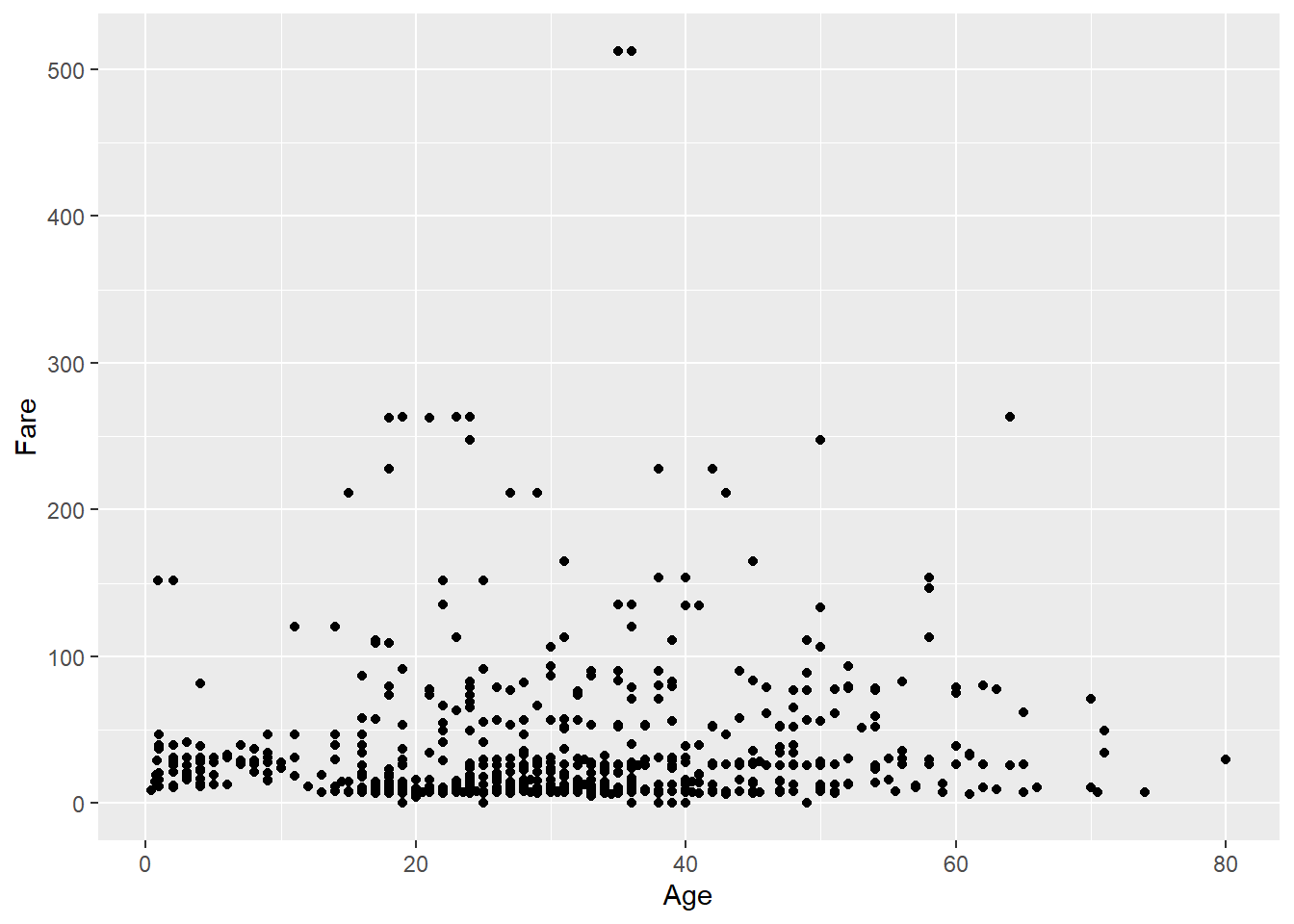

# Specifying aesthetics

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(mapping = aes(x = Age, y = Fare))

Now the plot shows axes labeled with the correct variable names, but

still no data points, because we still have not yet defined how to

represent the data visually. To do that, we add a

geometry, which tells ggplot2 how to

display the data. For a scatter plot (where each point represents

one observation), we use geom_point():

# Add geometry to create a scatter plot

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(mapping = aes(x = Age, y = Fare)) +

geom_point()

Notice that in ggplot2, we add layers to the plot using

the plus sign (+), not the pipe (%>%)

used in dplyr. The result is a functional scatter plot.

To refine its appearance, we can customize the

theme, which controls non-data elements like

background color, grid lines, font sizes, and margins.

ggplot2 offers several built-in themes. In our original

example, we used theme_light():

# Create a graph with pipes - Data, Aesthetic, Geometry, Theme

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(mapping = aes(x = Age, y = Fare)) +

geom_point() +

theme_light()

The final plot looks exactly like the one we presented at the

beginning of this section. This example demonstrates the modular

nature of ggplot2: each layer builds on the previous

one to produce the final visualization.

To summarize, every plot in ggplot2 consists of four

main components: data, aesthetics, geometry, and theme. A fifth,

optional component is facets, which allow us to split one plot into

multiple subplots based on a variable. We will now explore each of

these layers in more detail, including how facets work.

19.4 Data and Aesthetics

The first thing we need to consider before creating a plot is the

data we want to visualize. For instance, the Age and

Fare variables are numeric (continuous), so it makes

sense to visualize them with a scatter plot. A bar plot, on the

other hand, typically requires a categorical variable along with a

continuous one — so we wouldn’t be able to create a meaningful bar

plot using only Age and Fare, since the

values of one variable would be treated as different categories.

At this stage, we are only choosing which data and variables we want to use. We haven’t yet specified whether we want a scatter plot or a bar plot, or even which variable should go on the x-axis. When we talk about data, we’re simply referring to the data frame that will be used for plotting. In earlier examples, when we created the blank canvas, that was the step where the data was specified.

Once the dataset is chosen, we decide on the aesthetics,

meaning which variables will be mapped to visual elements of the

plot. Aesthetics include everything we write inside the

aes() function. In the previous example, we included

Age and Fare in aes().

Although we didn’t see any shapes on the plot at that point, we

could already see the x and y axes labeled, meaning those aesthetics

have been mapped.

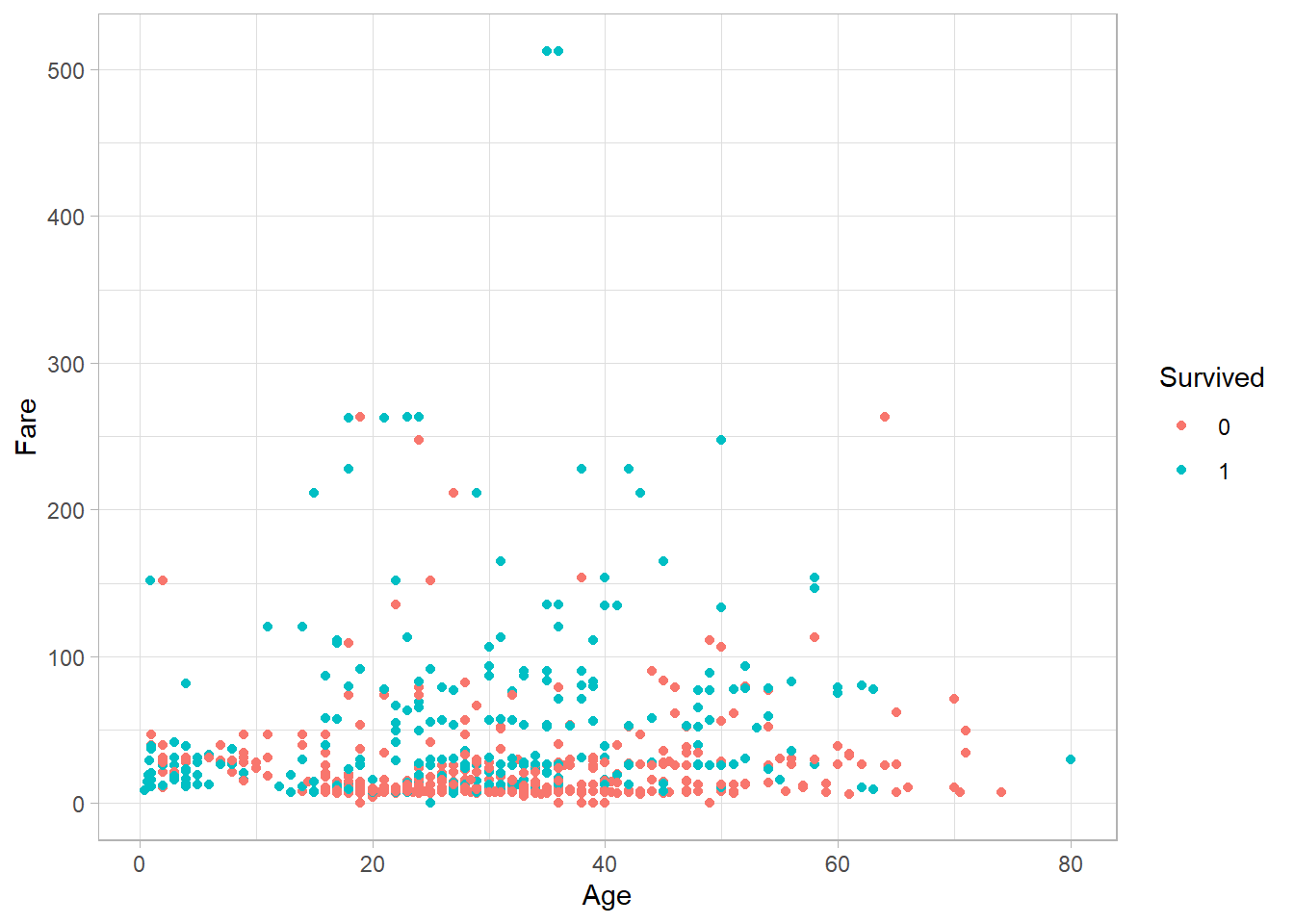

Besides the x and y axes, we can map more variables to additional

aesthetics while still keeping the plot two-dimensional. For

instance, we can add the Survived variable to color the

points in the scatter plot:

# Scatter plot with color mapped to a variable

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Age,

y = Fare,

color = Survived)) +

geom_point() +

theme_light()

Each point now has a color based on the corresponding survival status. Similarly, we can map variables to other aesthetics:

-

fill: fills an area with color (used in bars, boxplots, etc.) -

shape: changes the shape of the point -

alpha: adjusts transparency -

size: adjusts the size of points or lines

Depending on the data type, these mappings may or may not make sense, so it’s worth experimenting with different combinations to explore their effects.

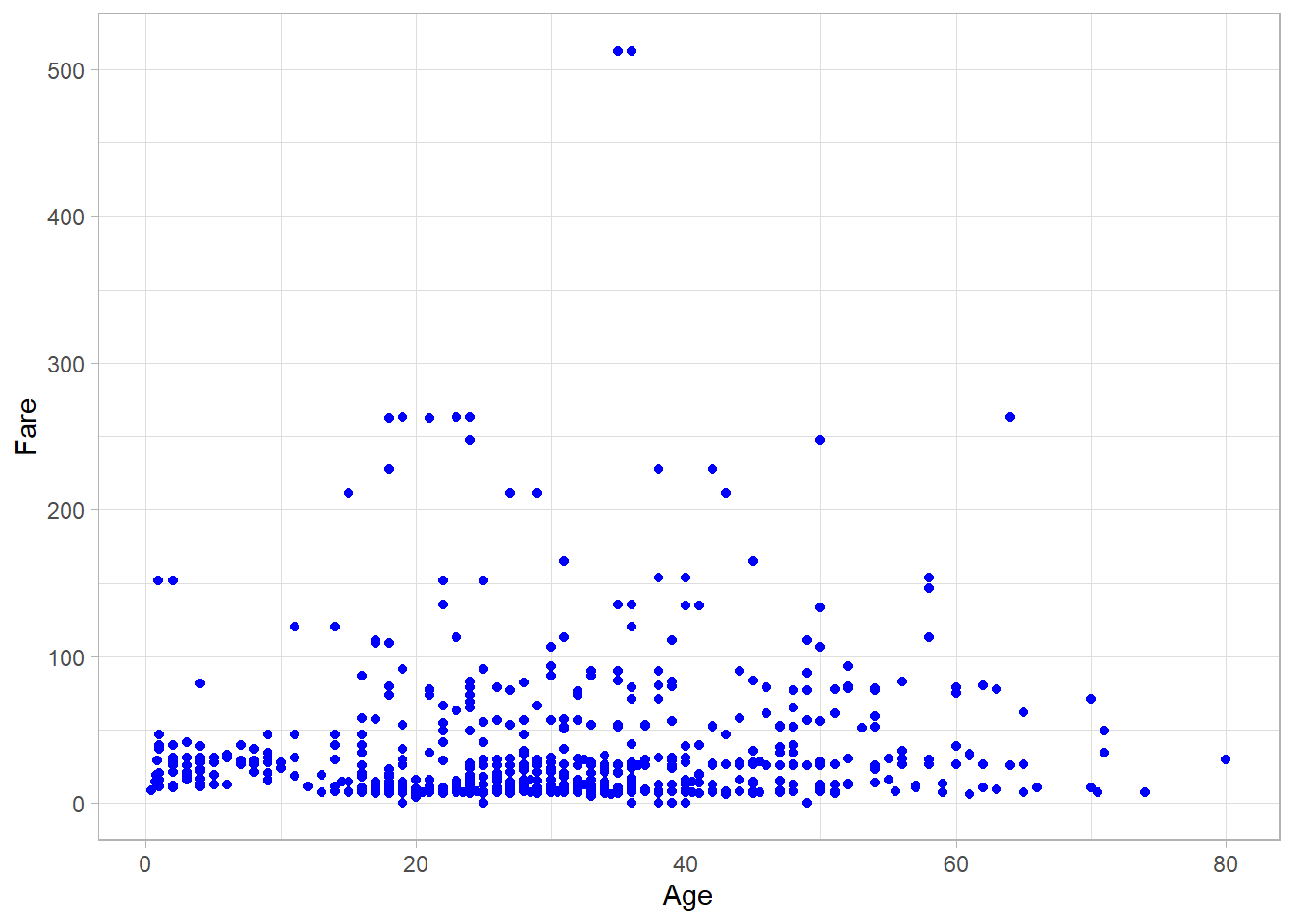

If instead we want to assign fixed values to these aesthetics (not

based on a variable), we do this outside of the

aes() function, inside the corresponding

geom_*() layer. For example, here we set all points to

blue, manually:

# Scatter plot with color set to a fixed value

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Age,

y = Fare)) +

geom_point(color = "blue") +

theme_light()

It might seem confusing at first, but the rule is simple:

-

If the aesthetic is mapped to a variable → put it inside

aes() -

If the aesthetic is set to a fixed value → put it outside

aes()

It is important to note that we can specify aesthetics either in the

ggplot() function or inside the

geom_point() function. When aesthetics are defined in

ggplot(), they are inherited by all subsequent layers

(geoms); we will see later in this chapter how to add multiple

geoms. In contrast, when aesthetics are specified inside a specific

geom_ function, they apply only to that particular

layer.

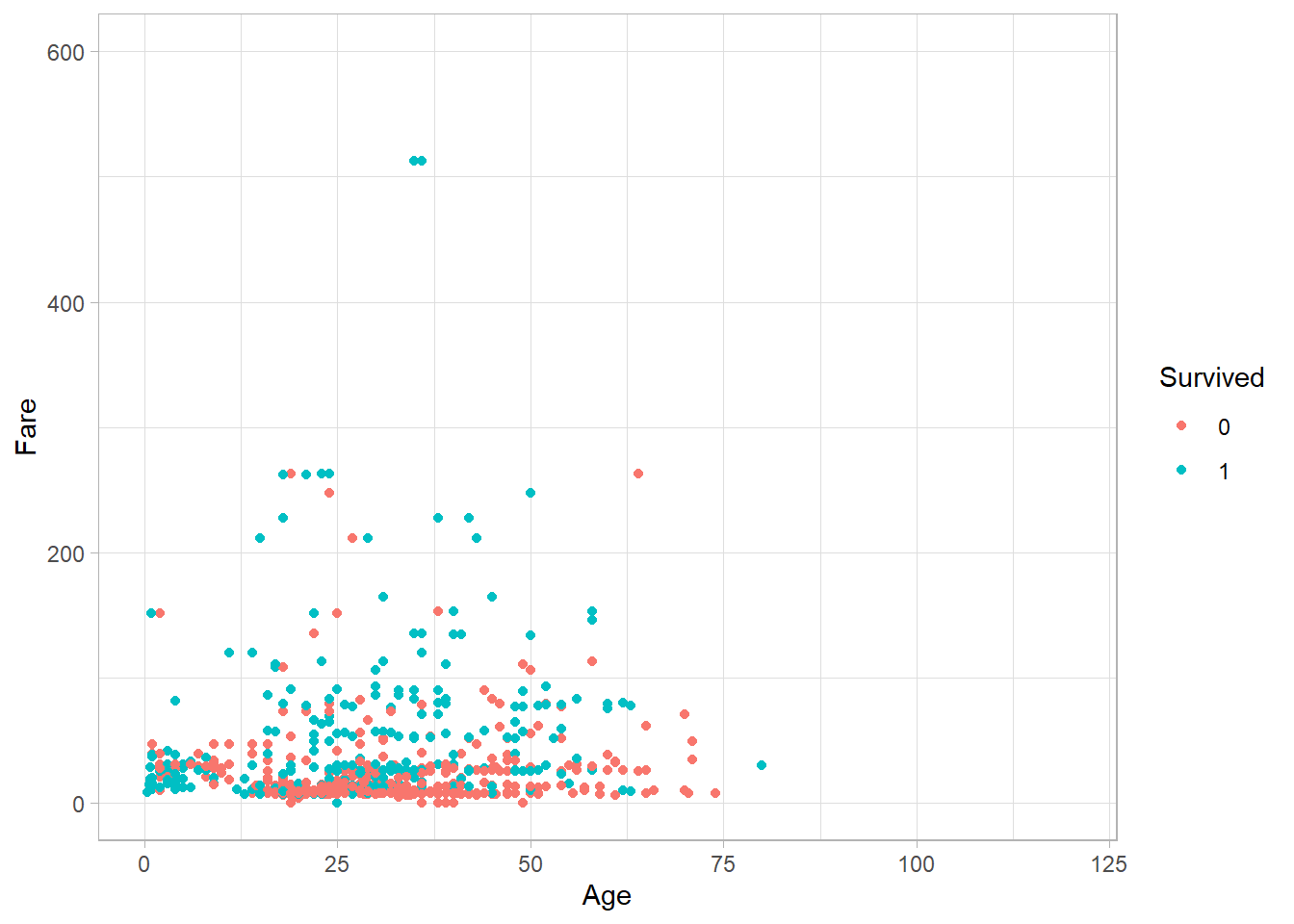

There are additional aesthetics we can adjust to control the

appearance of the plot. For example, we can limit the x-axis and

y-axis ranges using the xlim() and

ylim() functions respectively:

# Limit the range of the x-axis and the y-axis

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Age,

y = Fare,

color = Survived)) +

geom_point() +

theme_light() +

xlim(0, 120) +

ylim(0, 600)

This sets the x-axis range from 0 to 120 and the y-axis range from 0 to 600. Any points outside these limits will be omitted, and R will issue a warning when the code is executed.

We can also change how values are scaled using functions that start

with scale_*(). For example, to show the x-axis in

log-10 scale:

# Apply log10 transformation to the x-axis

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Age,

y = Fare,

color = Survived)) +

geom_point() +

theme_light() +

scale_y_log10()

We often want to add titles and axis labels to make our plots easier

to understand. This is done using the labs() function:

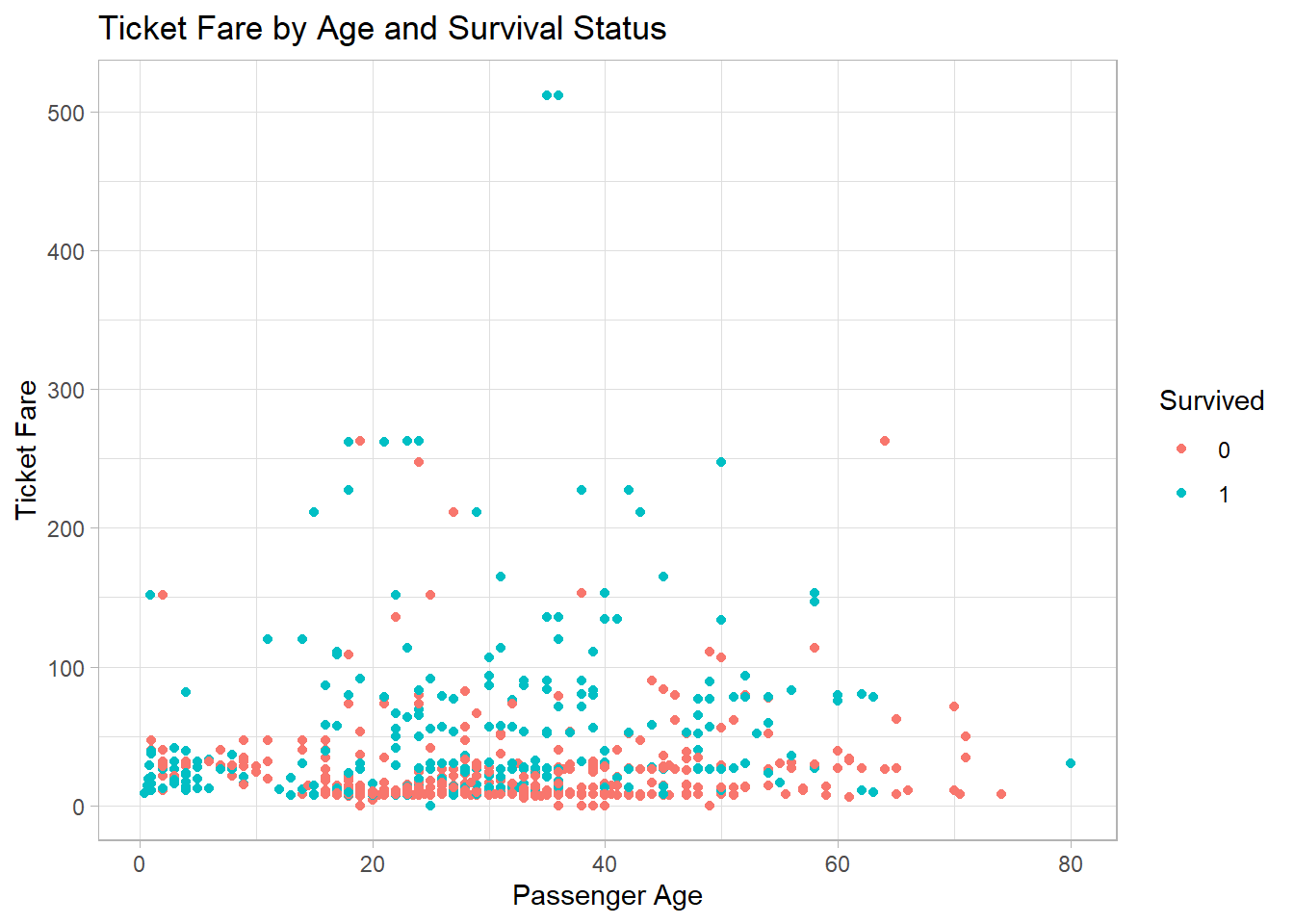

# Add custom axis labels and title

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Age,

y = Fare,

color = factor(Survived))) +

geom_point() +

theme_light() +

labs(

x = "Passenger Age",

y = "Ticket Fare",

color = "Survived",

title = "Ticket Fare by Age and Survival Status")

Here, labs() adds labels for the x-axis, y-axis,

legend, and title. Although not technically part of the core

aesthetics, labs() is conceptually linked to the

aesthetic layer because it describes how aesthetics are

communicated.

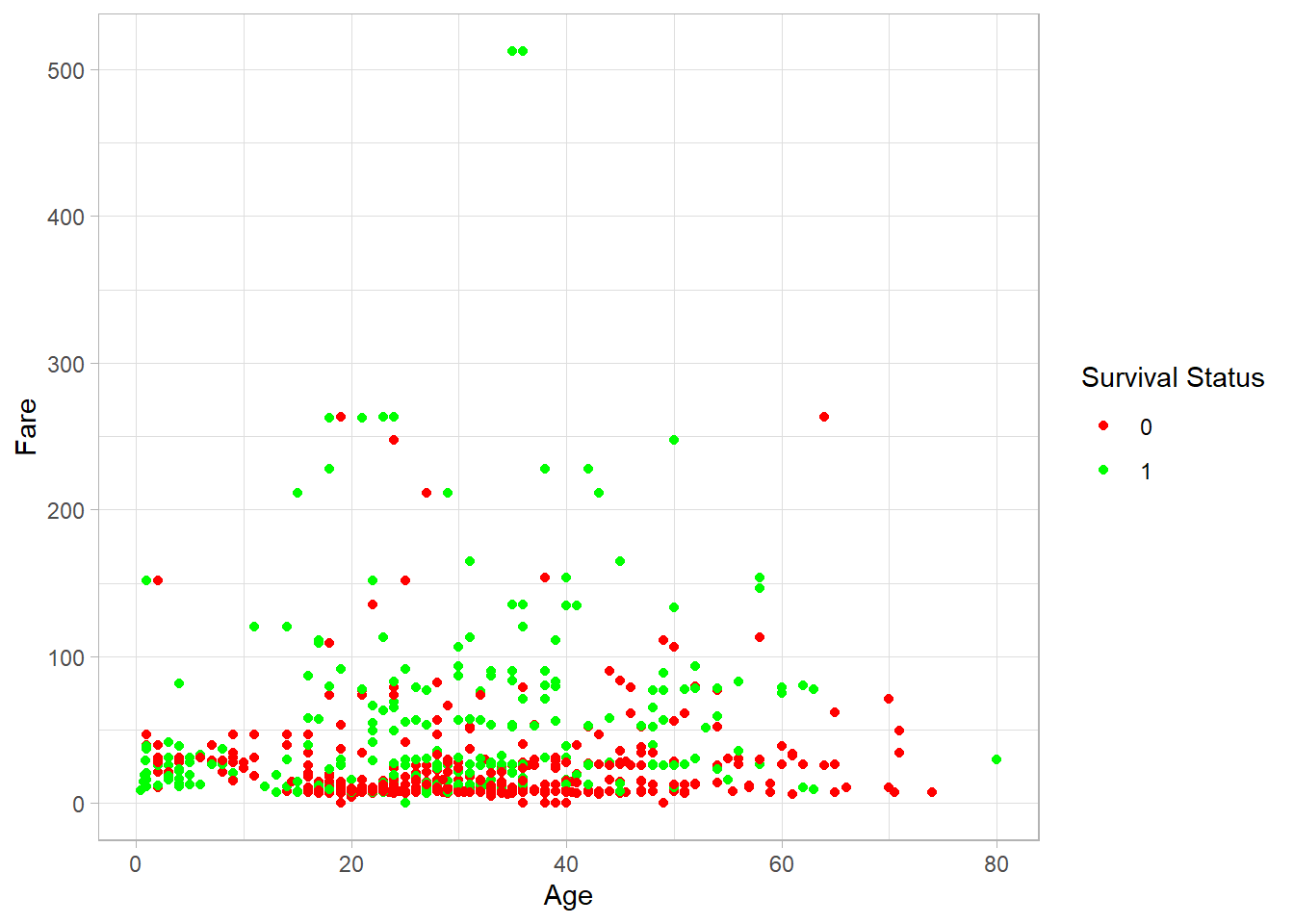

When a variable is mapped to an aesthetic, we can use the

scale_*_manual() family of functions to manually

control how values are displayed. Here’s how to change the colors

assigned to survival status:

# Manually set colors for the 'Survived' variable

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Age,

y = Fare,

color = factor(Survived))) +

geom_point() +

theme_light() +

scale_color_manual(values = c("0" = "red", "1" = "green")) +

labs(color = "Survival Status")

We can also manually set shapes, fill colors, transparency, and sizes using similar functions:

-

scale_fill_manual() -

scale_shape_manual() -

scale_alpha_manual() -

scale_size_manual()

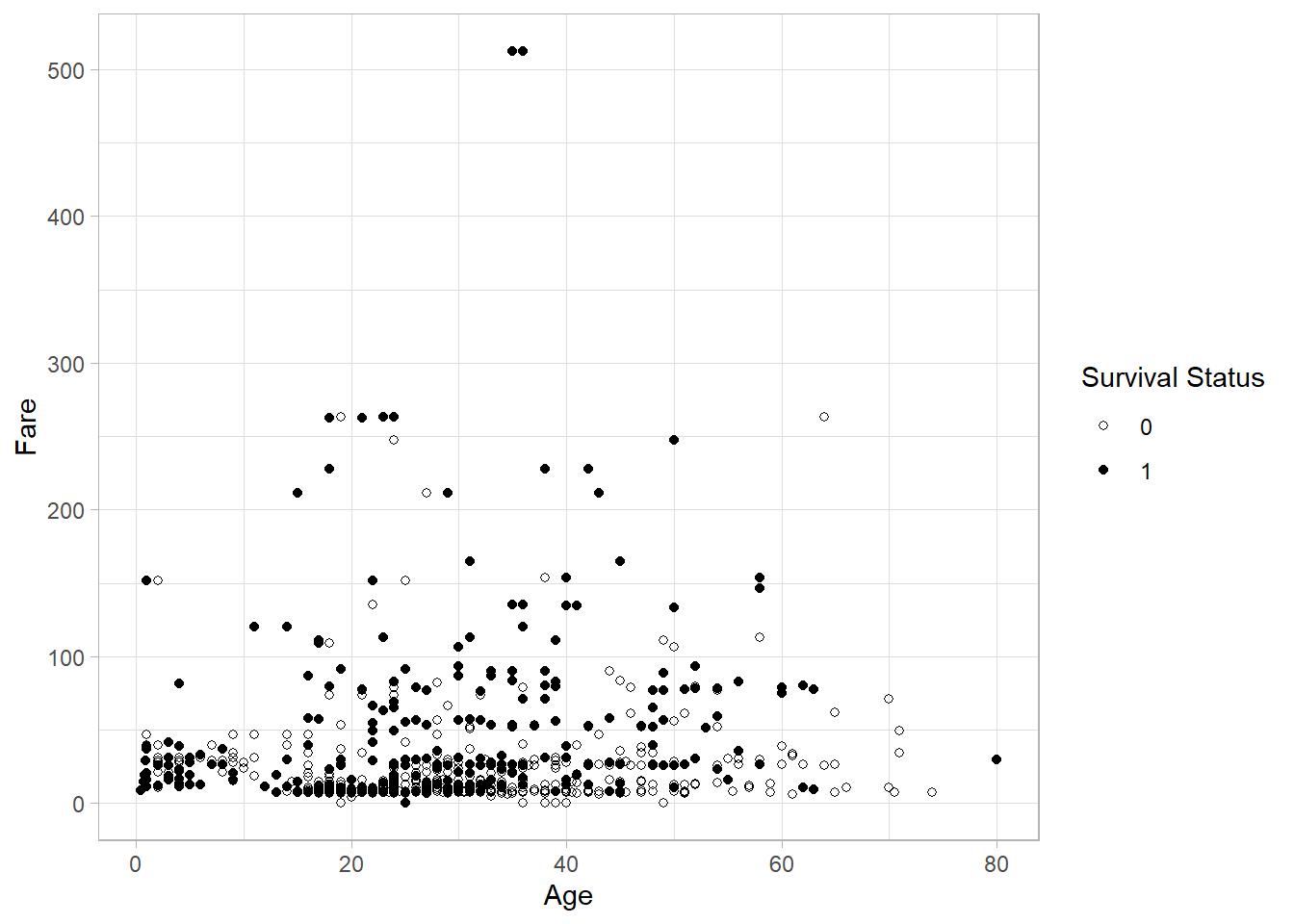

For example, setting custom shapes:

# Manually set shapes for the 'Survived' variable

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Age,

y = Fare,

shape = factor(Survived))) +

geom_point() +

theme_light() +

scale_shape_manual(values = c("0" = 1, "1" = 16)) +

labs(shape = "Survival Status")

These tools give us full control over how your aesthetics appear in the plot, allowing you to adapt your graph for clarity, emphasis, or even publication styling.

There are still more aesthetics available beyond those mentioned

above, depending on the type of plot and driving the visual effect

one aims for. The full list of available aesthetics can be found on

the

ggplot2 official documentation site

or by using the ?aes help command in RStudio.

19.5 Geometry

So far, we have specified the data and the aesthetics we want to use in a graph, but we have not yet specified what kind of plot we want to create. Should it be a scatter plot, a histogram, or a bar chart?

In ggplot2, we define the type of plot using a function

that starts with geom_*(). For example, earlier we used

geom_point() to create a scatter plot. We could have

used geom_line() to create a line plot instead.

(Although it might not yield any useful insights in our Titanic

data!) The geometry function determines the form of our

plot.

There are many types of geometries available in

ggplot2. In this section, we will focus on some of the

most common ones, namely:

Scatter plots

Histograms and density plots

Bar plots

Box plots

Line plots

19.5.1 Scatter Plots

We already created a scatter plot at the beginning of this chapter

using the geom_point() function. A scatter plot is

ideal when we want to display two numeric variables on the axes.

We can add more variables to a scatter plot by changing an element

of the plotted points. For example, we previously used the

variable Survived to color the points - we could

similarly change shape.

19.5.2 Histogram and Density Plots

In the Statistical Distributions chapter, we introduced histograms and density plots as tools to visualize the distribution of a variable. Now let’s see how to create them.

We use geom_histogram() and

geom_density() to generate histogram and density

plots respectively. These are one-dimensional plots, so we only

need to specify the x variable inside the

aes() function:

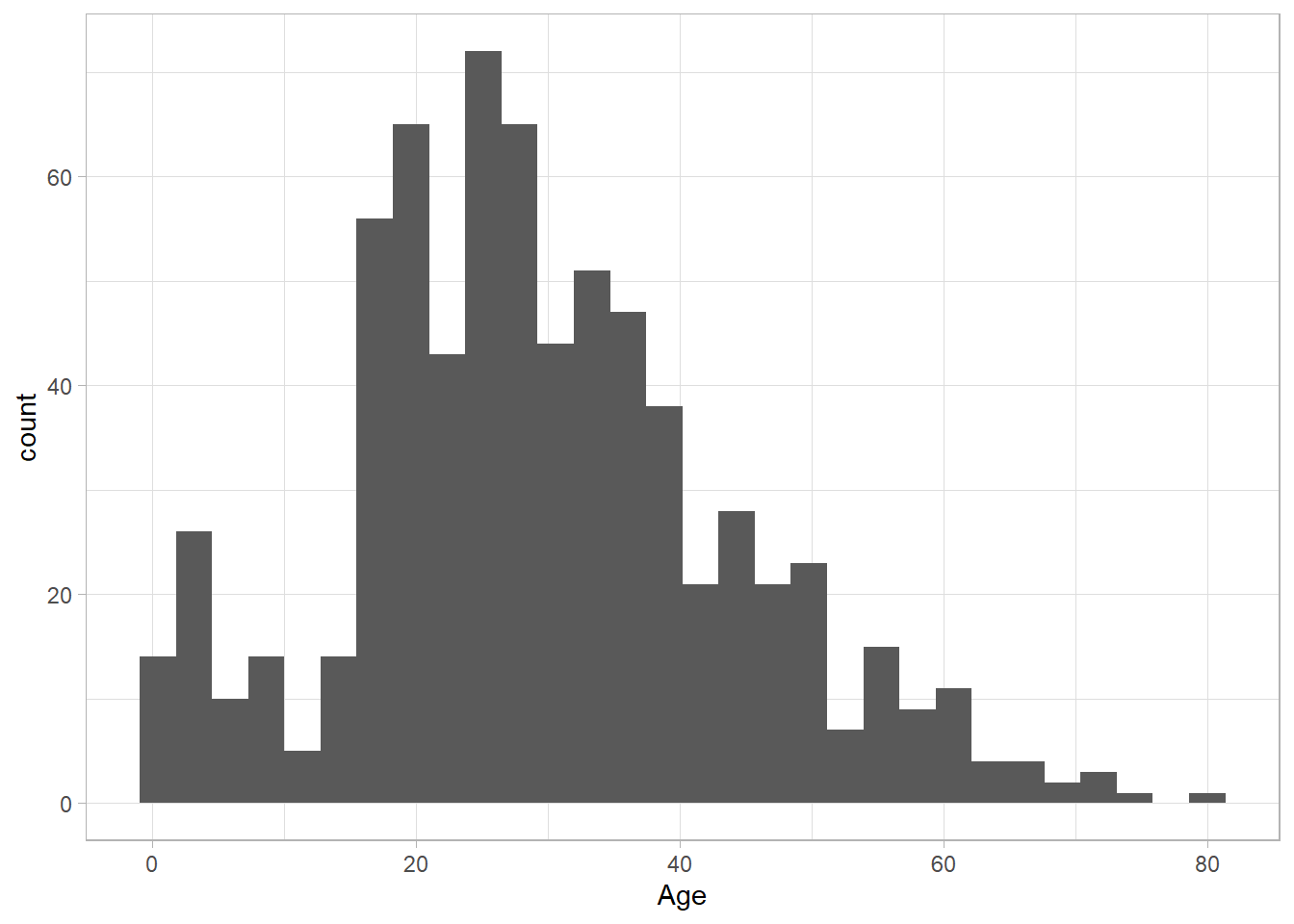

# Histogram of Age

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Age)) +

geom_histogram() +

theme_light()

The distribution of Age looks roughly normal. We can change the

granularity of the histogram by using the (number of)bins

or binwidth arguments in

geom_histogram(). We only need to set one of the two,

as the other one will be set automatically:

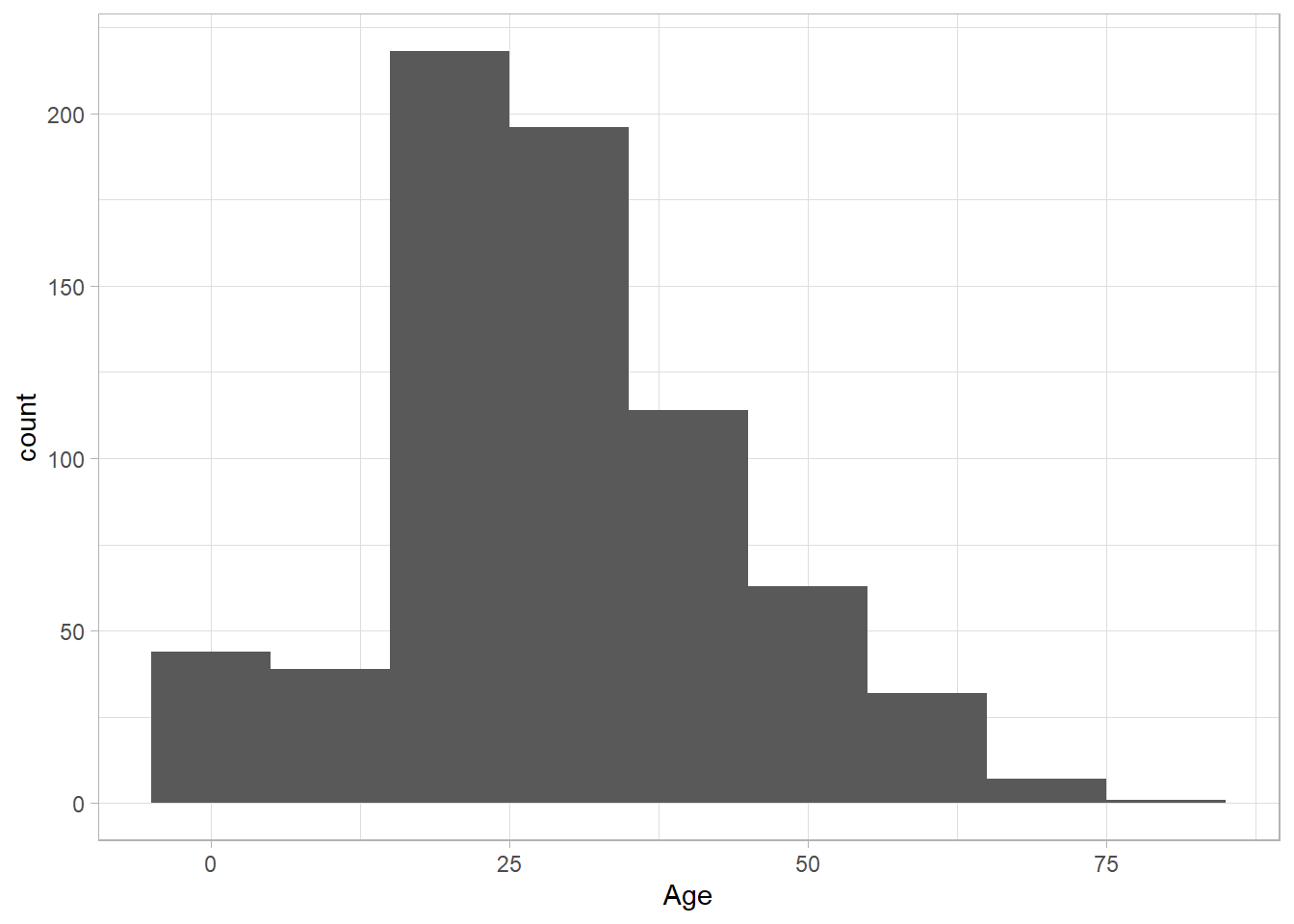

# Histogram with 5 bins

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Age)) +

geom_histogram(bins = 5) +

theme_light()

# Histogram with bin width of 10

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Age)) +

geom_histogram(binwidth = 10) +

theme_light()

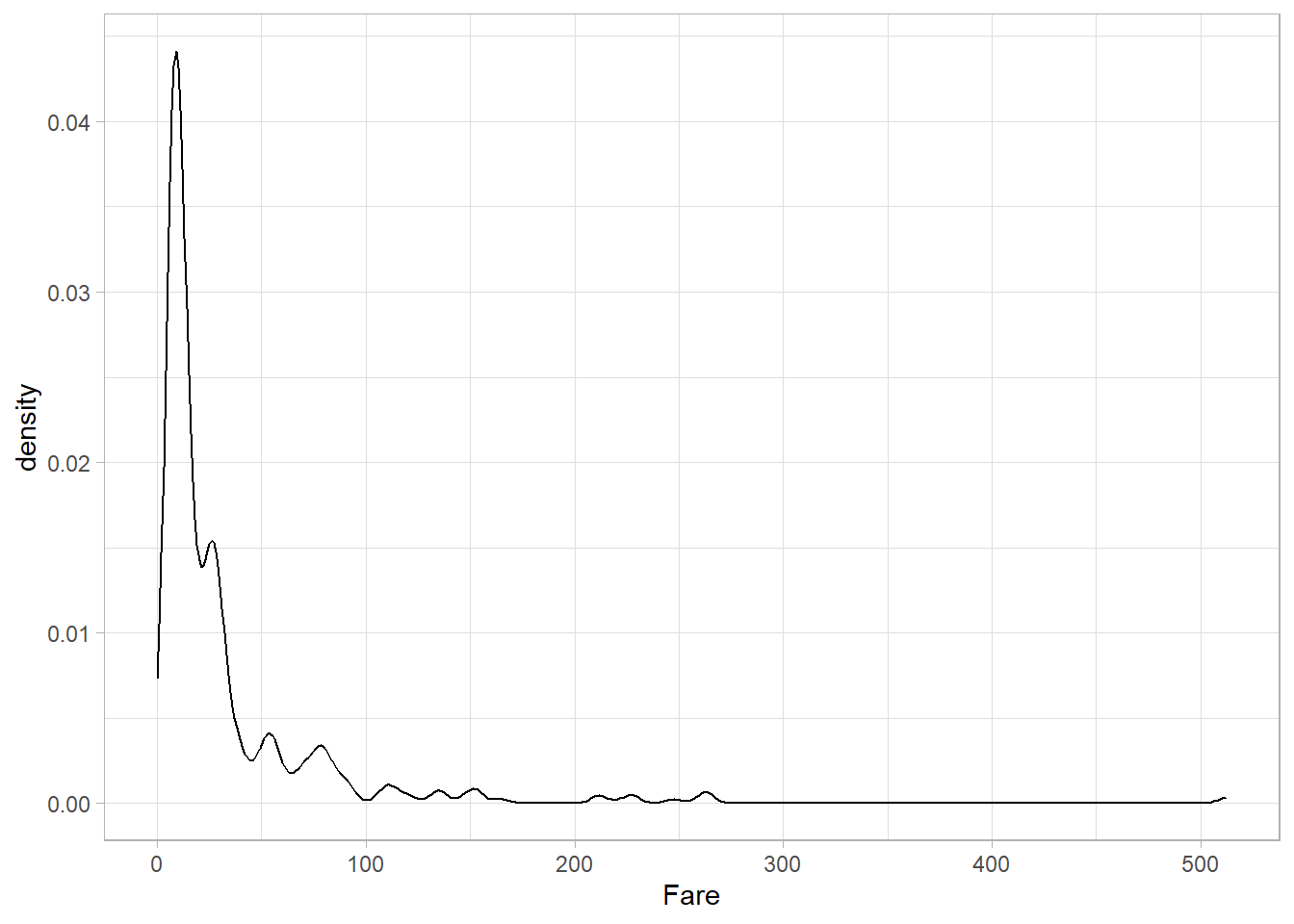

We can also explore the distribution of Fare, using a

density plot.

# Density Plot of Fare

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Fare)) +

geom_density() +

theme_light()

The variable Fare seems to follow a log-normal

distribution, with a long right tail.

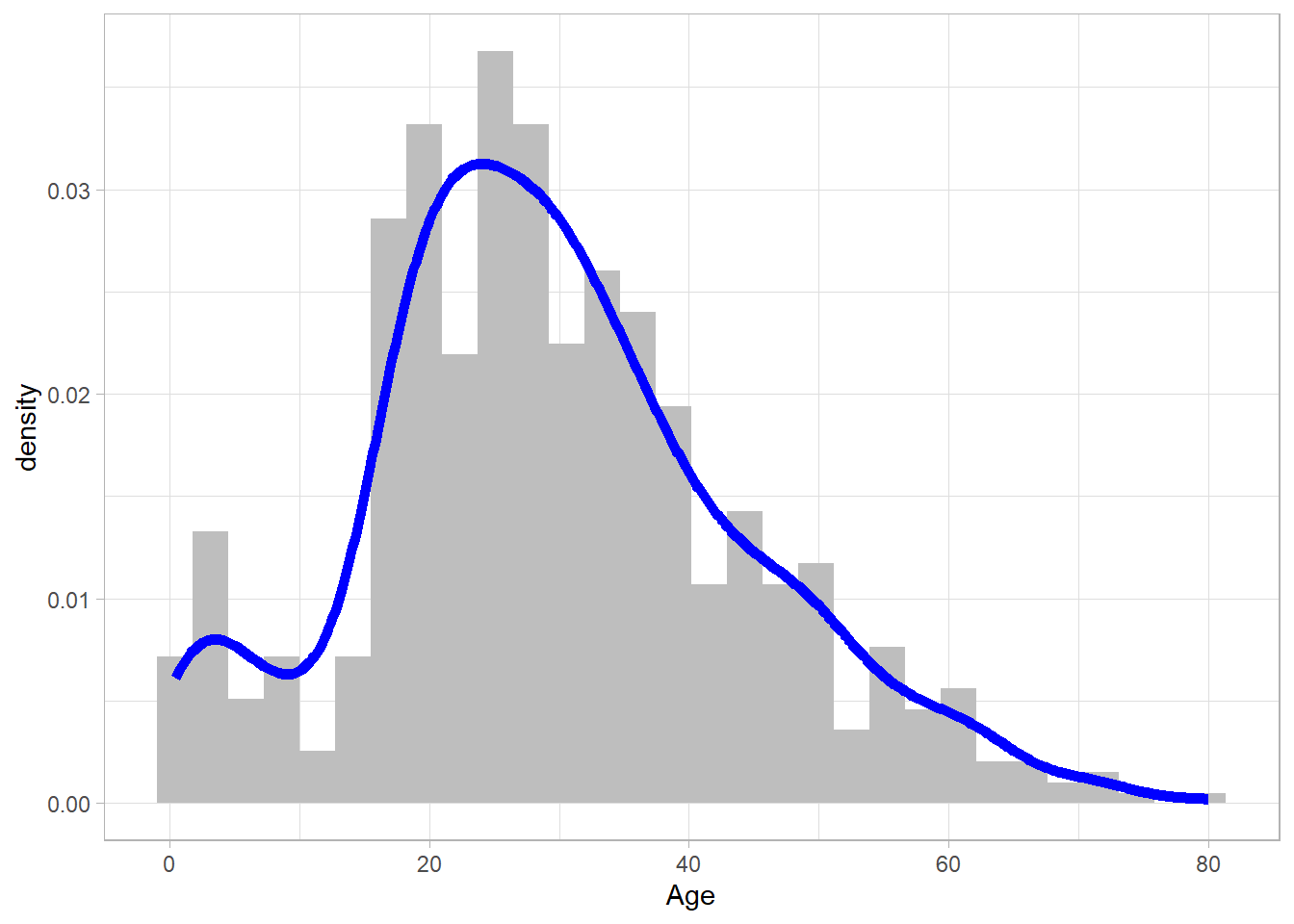

We can also combine these two types of geometries into one plot —

but in that case, we need to manually specify the y-axis. A

histogram shows counts on the y-axis, while a density plot shows

densities. To combine them, we use both

geom_histogram() and geom_density(), and

set the y aesthetic inside aes() to the

somewhat unusual expression ..density... This special

notation tells ggplot2 to scale the histogram so that

it represents a density rather than raw counts, allowing it to

align correctly with the density curve. We also modify the

appearance to make the plot clearer and demonstrate how different

aesthetics can be combined:

# Combined Histogram and Density Plot

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Age, y = ..density..)) +

geom_histogram(fill = "grey") +

geom_density(size = 2, color = "blue") +

theme_light()

19.5.3 Bar plots

Bar plots are an excellent choice for visualizing categorical

data. To create a bar plot, we use the

geom_bar() function. As with histograms and density

plots, we need to include only one variable on the x-axis. Let’s

plot the Survived variable:

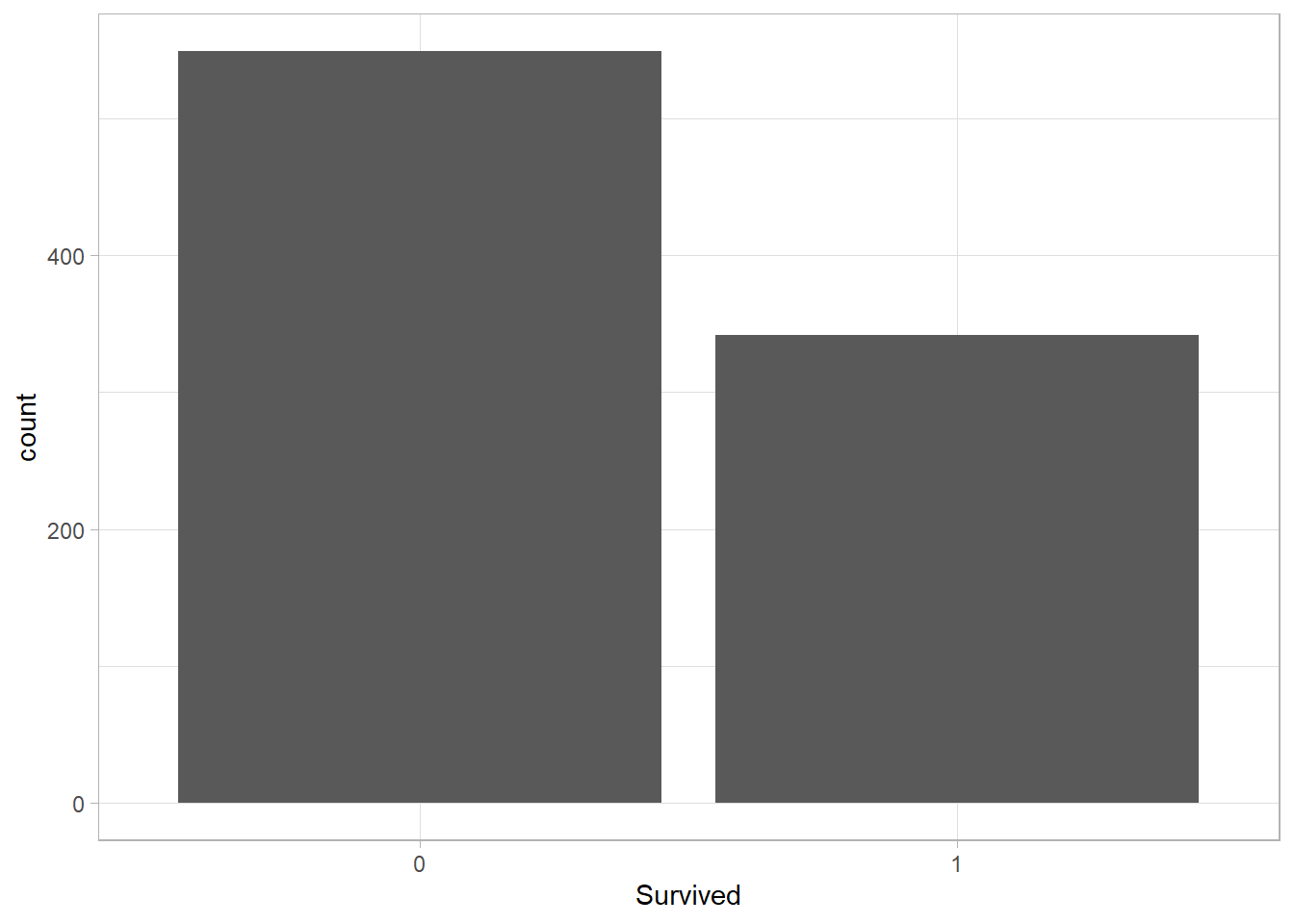

# Bar plot

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Survived)) +

geom_bar() +

theme_light()

Similar to geom_histogram(), the y-axis here

represents the number of observations. In fact, a bar plot can be

thought of as a histogram for categorical variables, where each

“bin” corresponds to a specific category. This plot shows that

most passengers on the Titanic did not survive.

Instead of plotting counts on the y-axis, we may sometimes want to

show a summary statistic. For instance, the average ticket price

(Fare) within each category. In this case, the x-axis

still displays the categories, but the y-axis will show a

numerical value. To do this, we use the

group_by() and summarize() functions

from the dplyr package to transform the data before

plotting. While this is not strictly part of ggplot2,

it’s an important reminder that data often needs to be manipulated

into the right shape before plotting.

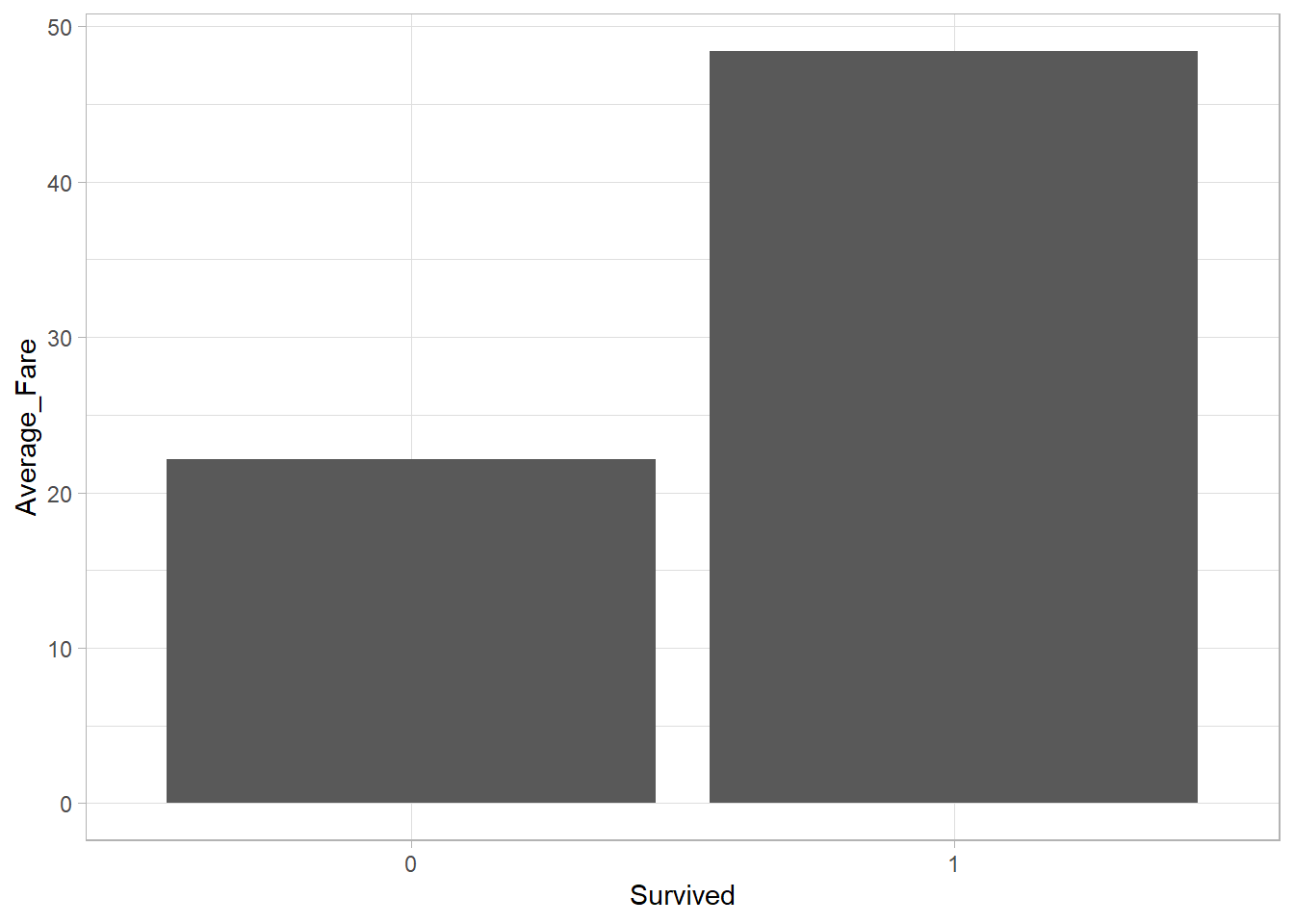

Let’s first compute the average ticket price for each category of

Survived:

# Average fare per category

average_fare <- titanic_subset %>%

group_by(Survived) %>%

summarize(Average_Fare = mean(Fare))

# Print the results

average_fare # A tibble: 2 × 2

Survived Average_Fare

<fct> <dbl>

1 0 22.1

2 1 48.4

Now that we have a summary table, we can fill in both

x and y inside aes(), just

like we would for a scatter plot with two numeric variables.

However, geom_bar() won’t work when we explicitly

supply a y variable and so we use the

geom_col() function instead:

# Plot of Average Fare per Category

average_fare %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Survived, y = Average_Fare)) +

geom_col() +

theme_light()

The average ticket price among survivors was higher than among non-survivors. This is an interesting insight as it may suggest that passengers who paid more had a higher priority when boarding the life boats or were located in more favorable areas of the ship (closer to the life boats perhaps?) before it sank.

19.5.4 Box plots

To visualize the distribution of a numeric variable, we previously used histograms and density plots. Another way to do this is with a box plot. As the name suggests, a box plot is essentially a… plot that includes a box, which represents the values close to the center of the distribution.

A box plot typically displays five summary statistics known as the five-number summary. These include:

-

Minimum: The smallest value

-

First Quartile (Q1): The 25th percentile, marking the lower edge of the box

-

Median (Q2): The 50th percentile, shown by the line inside the box

-

Third Quartile (Q3): The 75th percentile, marking the upper edge of the box

-

Maximum: The largest value

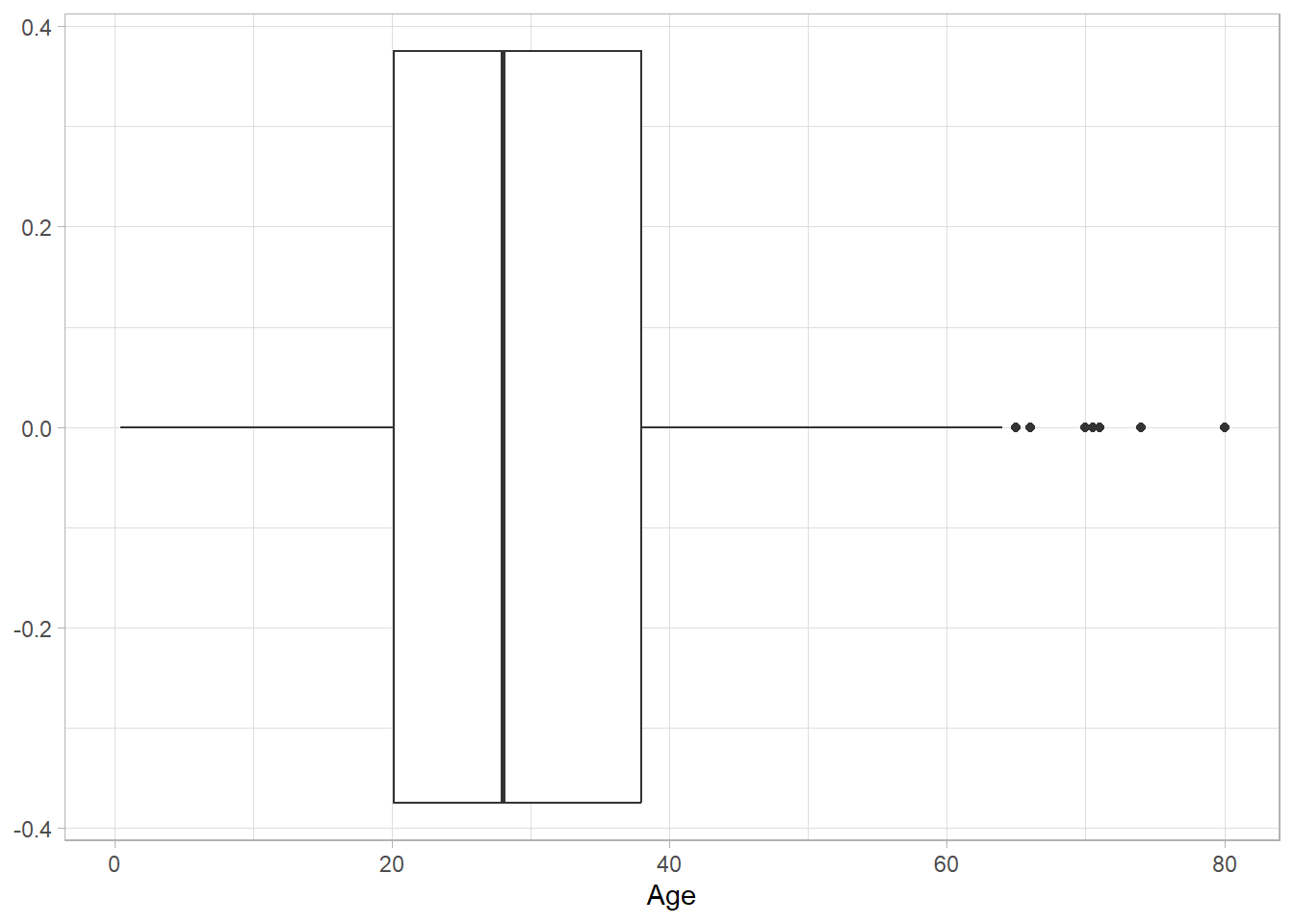

Let’s create a box plot for the Age variable using

geom_boxplot():

# Box plot

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Age)) +

geom_boxplot() +

theme_light()

The black horizontal line represents the median. The box contains

all values between the first and third quartiles, while the black

dots outside the box are outliers. This plot shows that the

Age variable is fairly symmetric, with just a few

outliers on the right-hand side.

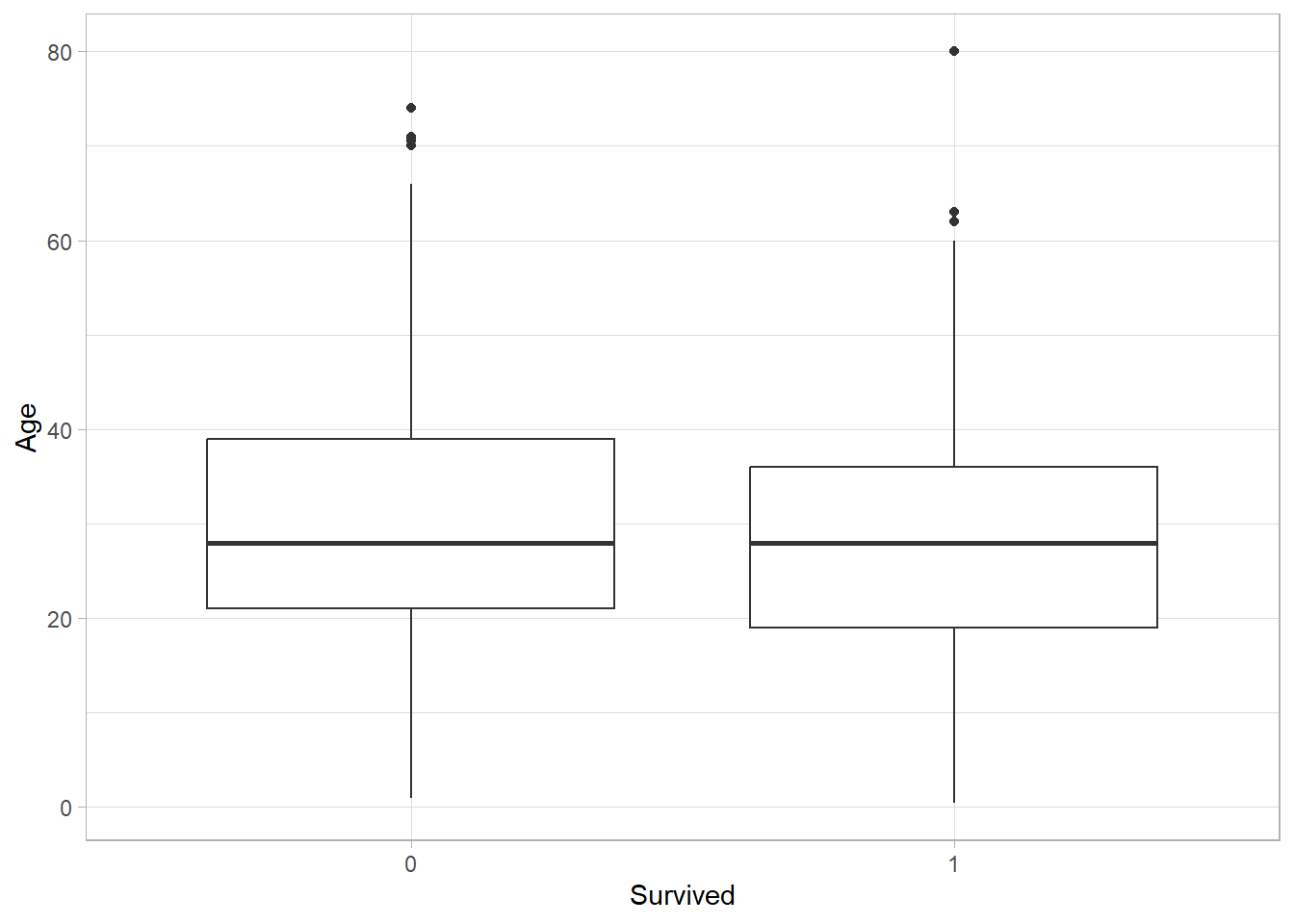

While histograms or density plots are preferred when visualizing

the distribution of a single variable, box plots are excellent for

comparing distributions across categories. To do this, we place

the numeric variable on the y-axis and the categorical variable on

the x-axis. For instance, the following plot shows the

distribution of Age across survival categories:

# Box plot

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Survived, y = Age)) +

geom_boxplot() +

theme_light()

The centers of the two distributions are nearly at the same level, with the distribution of non-survivors being slightly higher. This might reflect the fact that older passengers were slightly less likely to survive the disaster.

19.5.5 Line Plots

Line plots are another useful type of plot, although we haven’t encountered them in previous chapters. As the name suggests, a line plot connects data points with a line, helping to visualize trends or changes over time or ordered values.

To see how this works, let’s manually create a simple dataset with just a few data points:

# Create a simple data set

simple_data_set <- tibble(

x = c(10, 8, 13, 9, 11, 14, 6, 4, 12),

y = c(8.04, 6.95, 7.58, 8.81, 8.33, 9.96, 7.24, 4.26, 10.84))

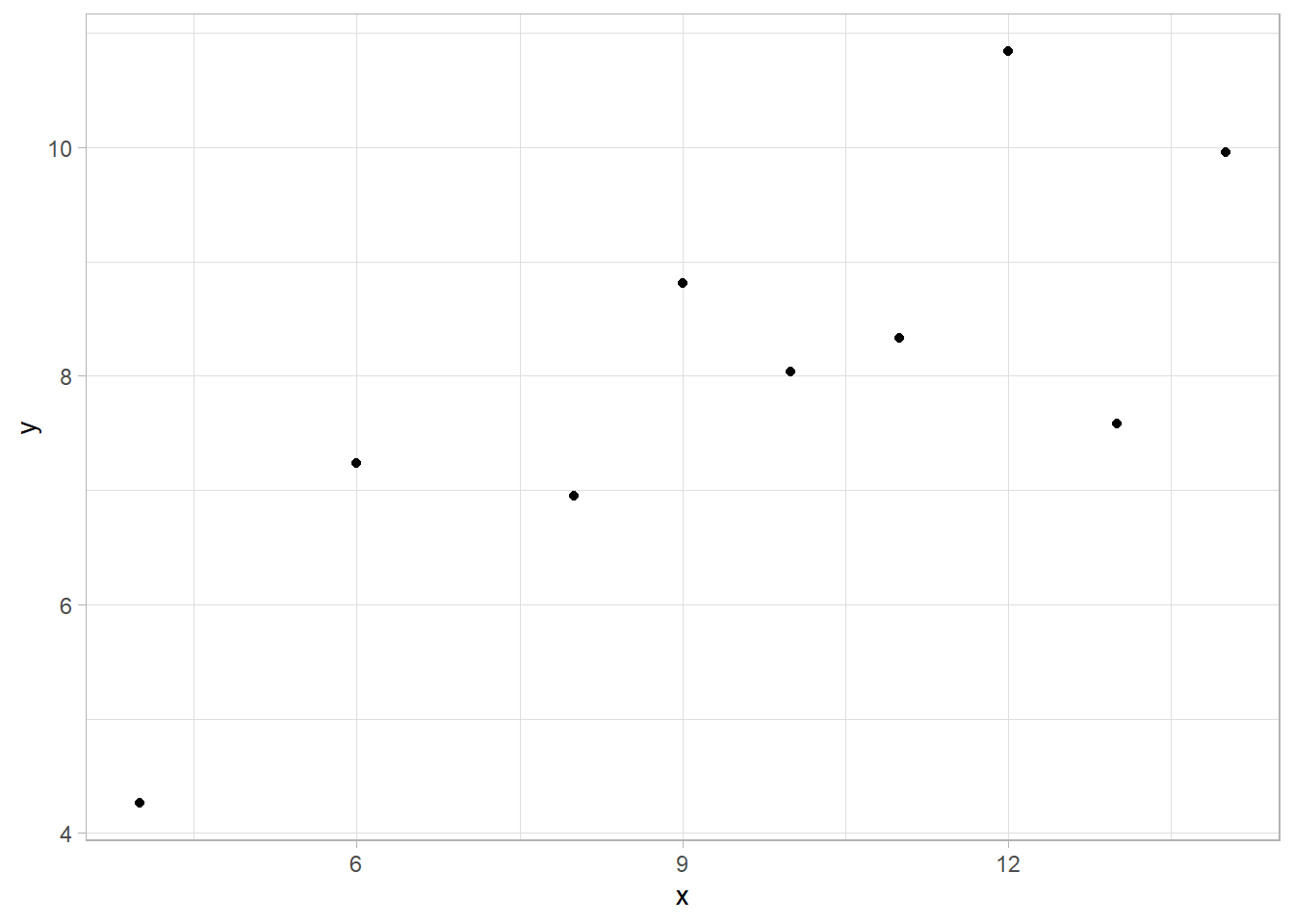

Since we have two numeric variables, we can first create a scatter

plot using the geom_point() function:

# Scatter plot

simple_data_set %>%

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y)) +

geom_point() +

theme_light()

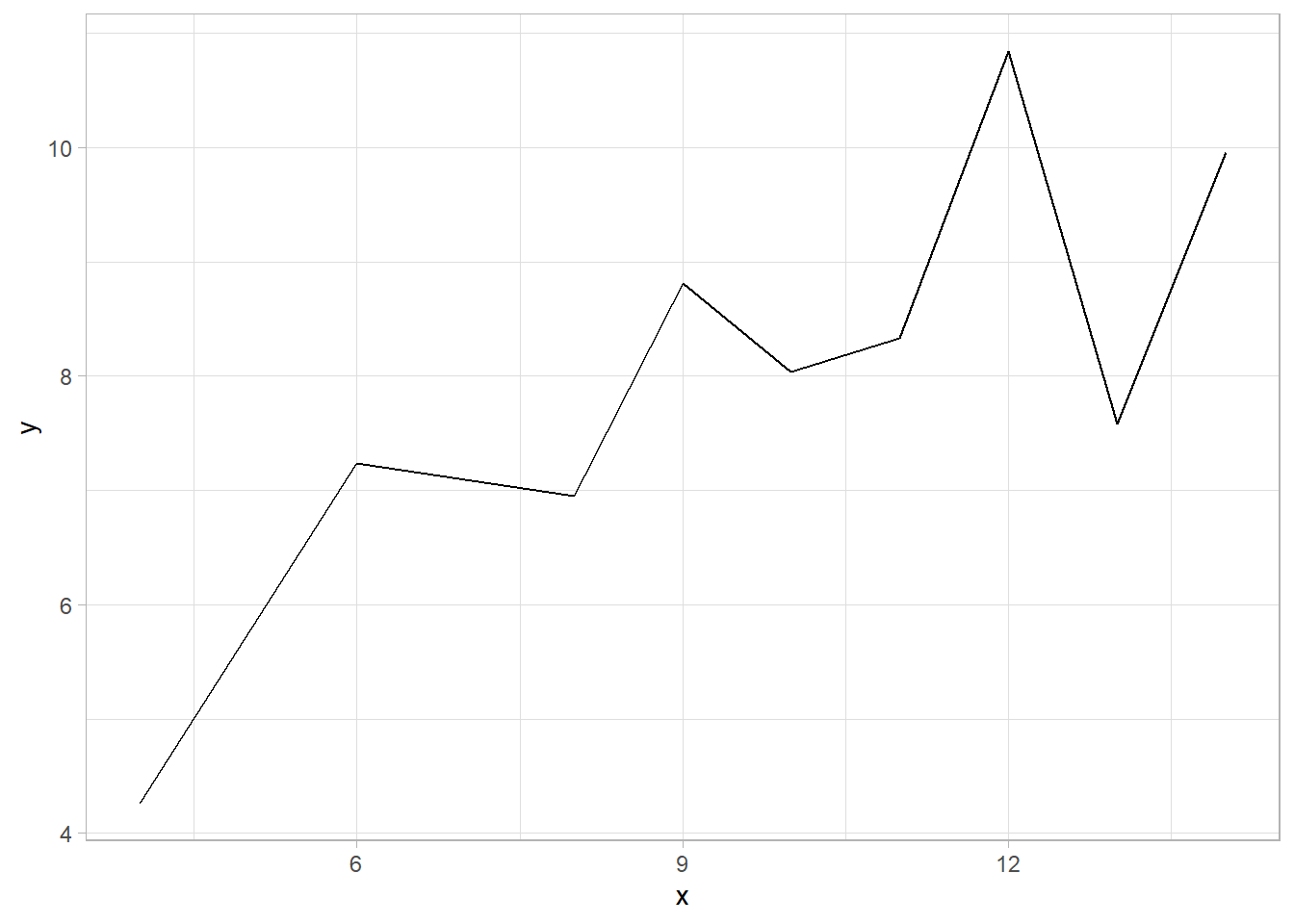

For a line plot, we use the geom_line() function

instead of geom_point(). This connects the data

points with a line:

# Line plot

simple_data_set %>%

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y)) +

geom_line() +

theme_light()

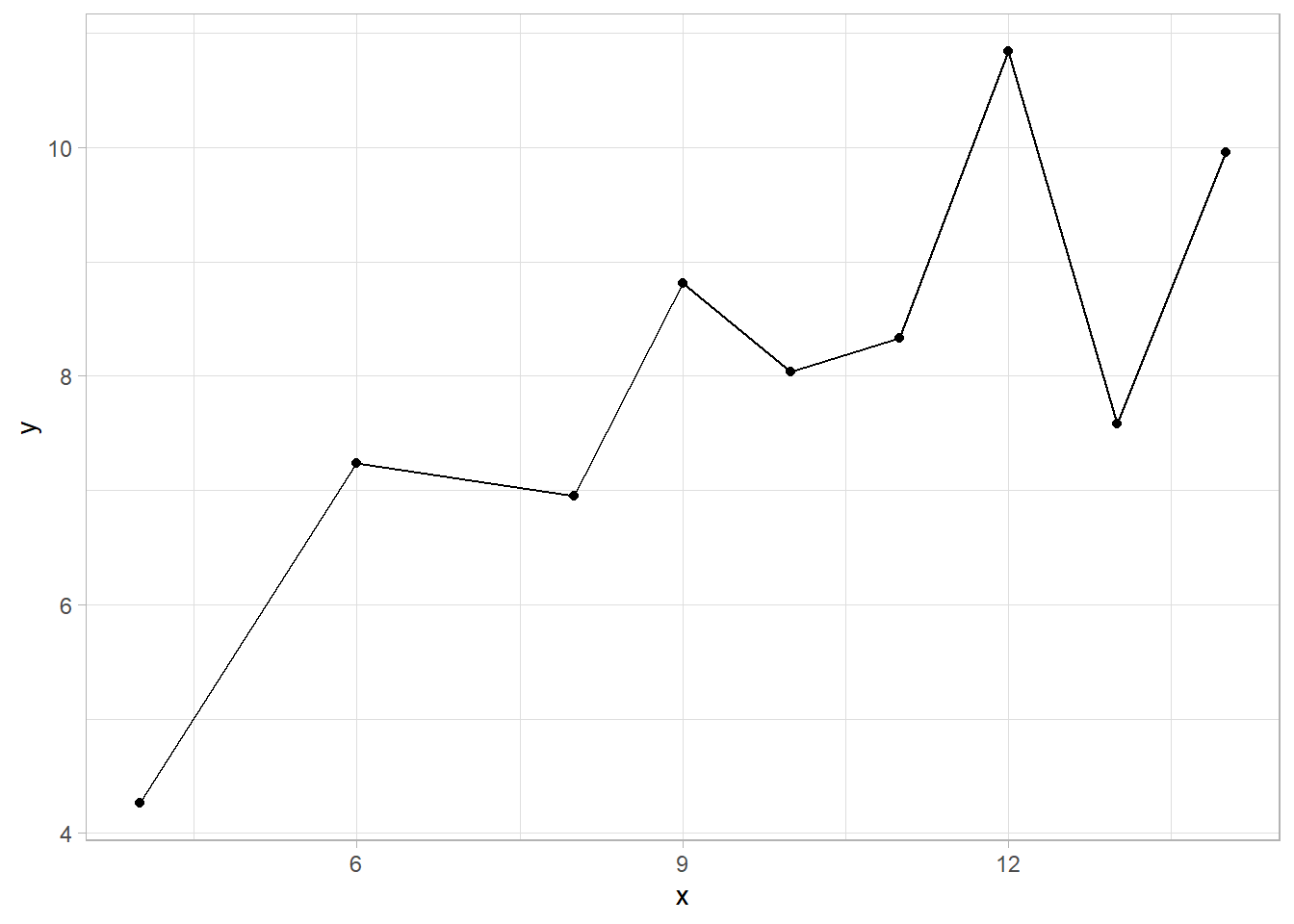

In the line plot above, the data points are not shown—only the

line appears. To include both the individual points

and the connecting line, we simply add the

geom_point() function along with

geom_line():

# Scatter-Line plot

simple_data_set %>%

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y)) +

geom_line() +

geom_point() +

theme_light()

This combined plot is often used to show both the trend (line) and the individual values (points), especially when the number of points is small and we want to see both clearly.

19.6 Facets

As we mentioned earlier, facets can be considered a separate, fifth plot element. Facets allow us to break down a plot into multiple subplots based on the values of at least one categorical variable. While we could always create separate plots manually for each category, facets provide a convenient way to generate multiple plots at once and display them side by side, making comparisons easier and more intuitive.

In ggplot2, there are two main functions for creating

facets: facet_grid() and facet_wrap(). The

key difference between them lies in how they organize the resulting

plots.

-

facet_grid()arranges plots in a grid format. One categorical variable is mapped to the rows and another to the columns. This is ideal for visualizing interactions between two categorical variables. -

facet_wrap(), in contrast, uses a single categorical variable and wraps the plots into a series, typically laid out in multiple rows or columns. This is especially useful when there’s only one categorical variable involved.

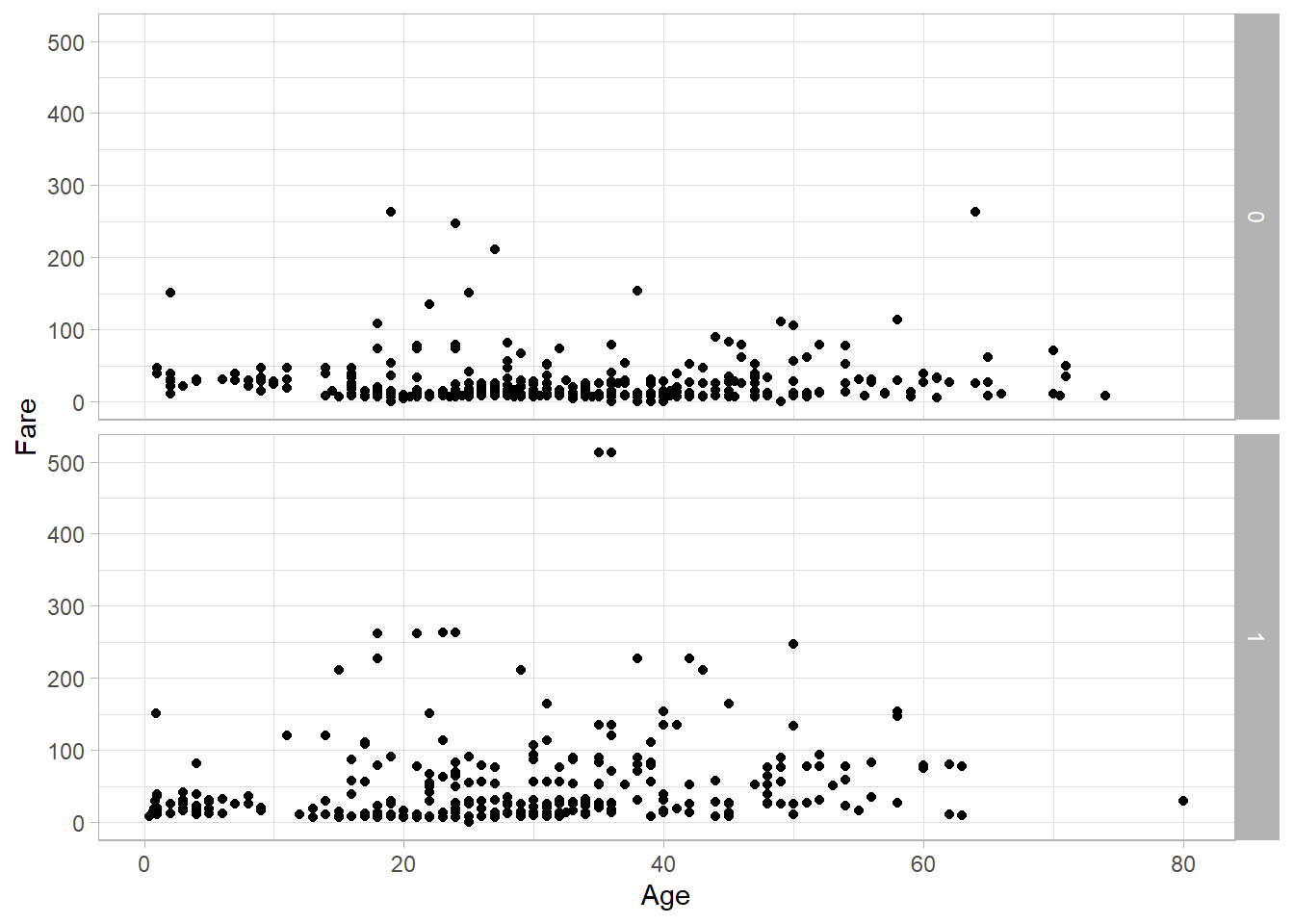

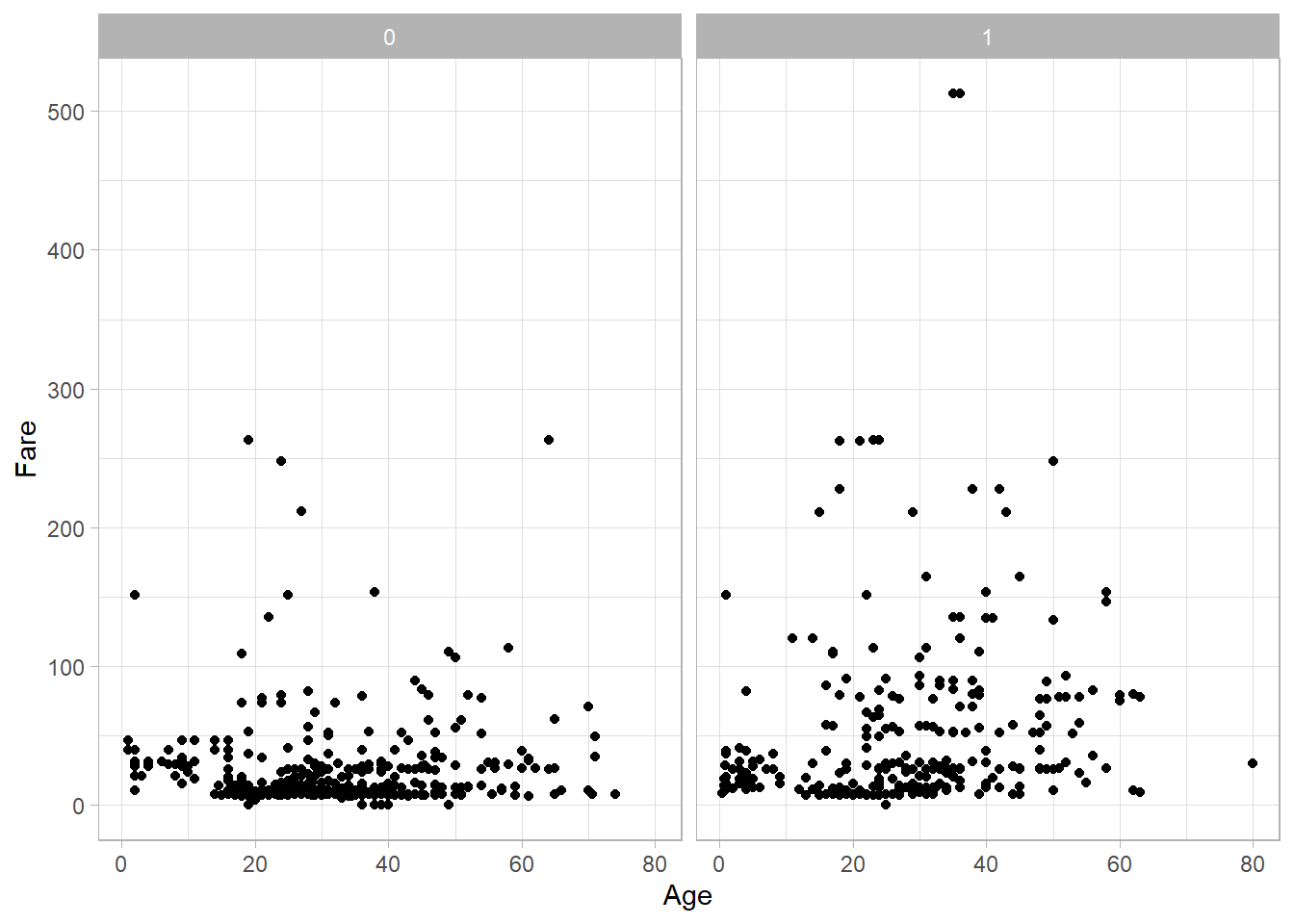

To understand how these two functions work, let’s revisit the

scatter plot we created earlier in the chapter. This time, we add

facet_grid() to break the plot into two separate

scatter plots—one for each category of the

Survived variable:

# Scatter plots with grid (rows)

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Age, y = Fare)) +

geom_point() +

theme_light() +

facet_grid(Survived ~ .)

With both facet_grid() and facet_wrap(),

we use the tilde (~) symbol to define the layout of the

plots. Since Survived appears on the left-hand side

here, the plots are arranged in rows. If we want the plots arranged

in columns, we simply place Survived on the right-hand

side:

# Scatter plots with grid (columns)

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Age, y = Fare)) +

geom_point() +

theme_light() +

facet_wrap(. ~ Survived)

Using facet_wrap() instead yields a similar result when

dealing with only one categorical variable:

# Scatter plots with wrap

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Age, y = Fare)) +

geom_point() +

theme_light() +

facet_grid(. ~ Survived)

In this case, because Survived has only two levels,

both functions produce nearly identical visual outputs.

To better understand the differences between these two functions,

let’s now introduce a second categorical variable. We’ll create an

Age_Category variable that classifies passengers as

“Underage” (under 18), “Adult” (18 or older), or “Missing” (if the

age is not available):

# Create Age_Category

titanic_subset <- titanic_subset %>%

mutate(

Age_Category = case_when(

is.na(Age) ~ "Missing",

Age >= 18 ~ "Adult",

TRUE ~ "Underage"))

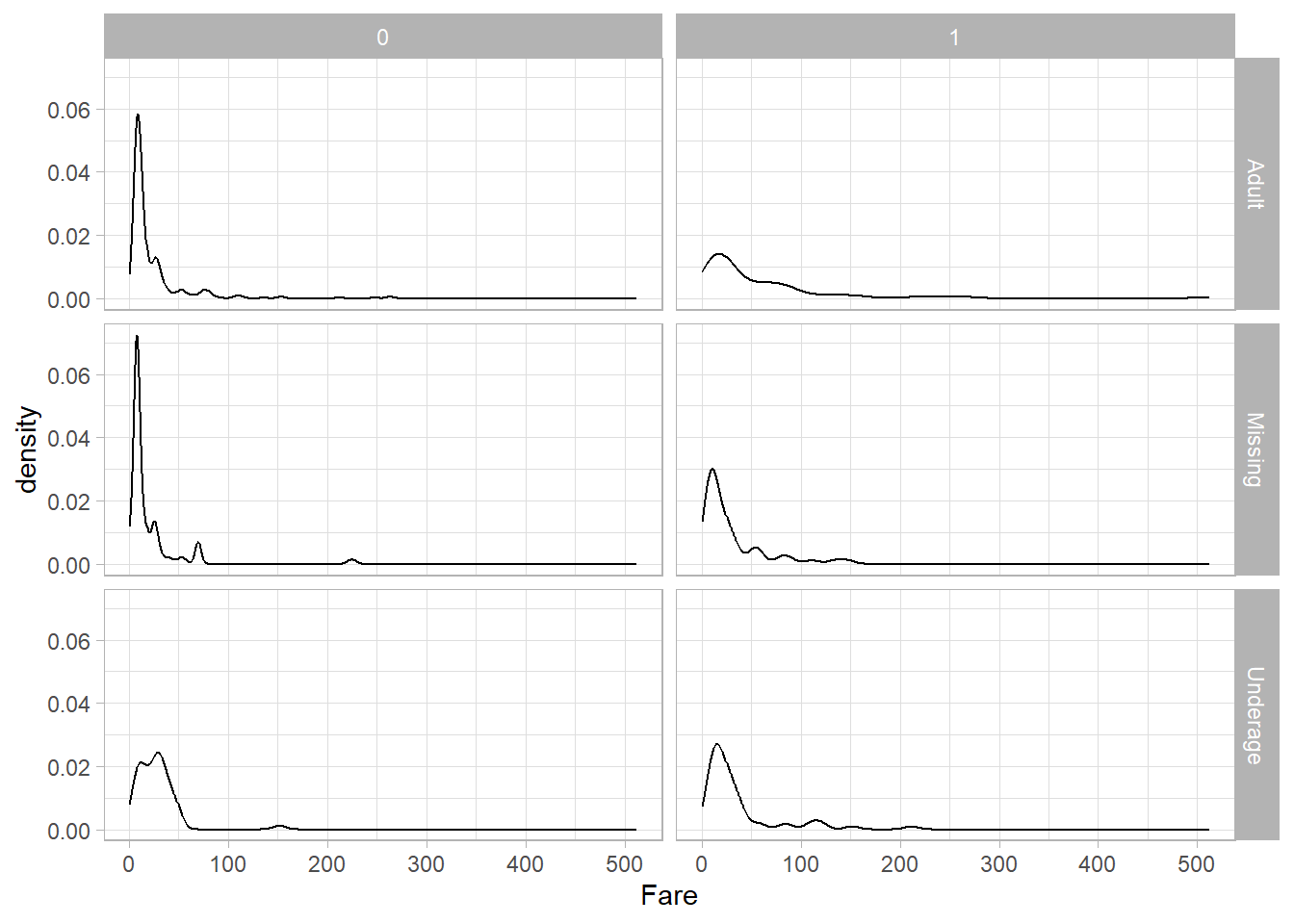

Now, let’s use facet_grid() to create a grid of density

plots for Fare, with Age_Category on the

rows and Survived on the columns:

# Density plots with grids

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Fare)) +

geom_density() +

theme_light() +

facet_grid(Age_Category ~ Survived)

This results in six separate density plots. The rows represent the age categories, and the columns represent the survival categories.

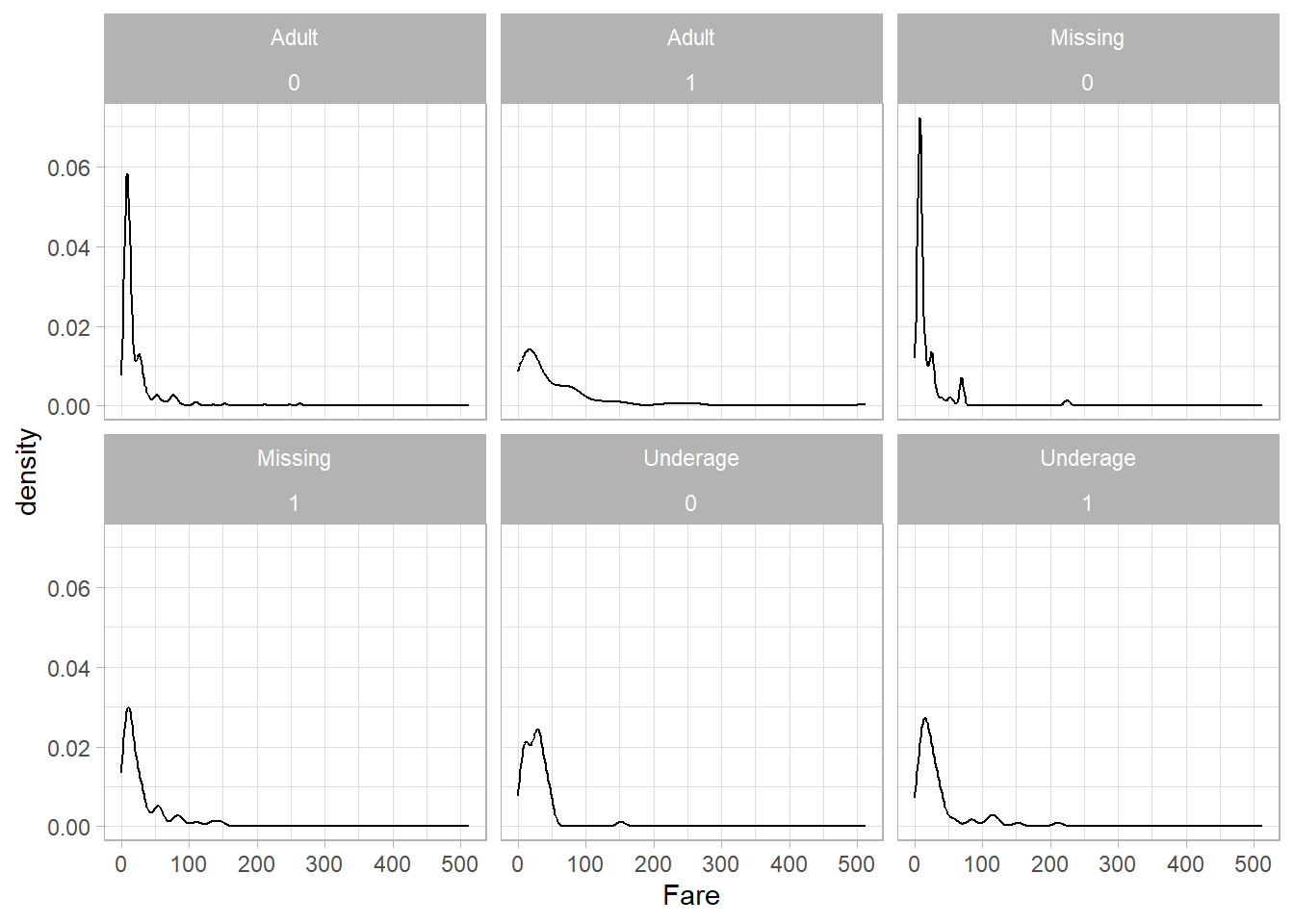

If we use facet_wrap() instead, the layout changes:

# Density plots with wraps

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Fare)) +

geom_density() +

theme_light() +

facet_wrap(Age_Category ~ Survived)

We still get the same six plots, but now each one is displayed as

part of a flexible layout with a combined label like

Age_Category = Underage, Survived = 1 at the top of

each panel. This makes facet_wrap() especially useful

when the combinations of variables don’t form a clean grid.

19.7 Theme

The ggplot2 package provides a default visual theme, as

we’ve seen in all our plots so far. However, we can change this

default theme by using one of the many alternatives included in the

package, or even by customizing a theme to match our own

preferences. In fact, we have already been using the

theme_light() function in our previous graphs to apply

a different look than the default one.

Playing with different themes is largely a matter of personal taste,

but the built-in themes in ggplot2 are generally high

quality and widely used. Choosing a theme helps ensure clarity and

consistency in the way your plots are presented.

Because nearly every visual element in a plot can be customized, we’ll focus on the basic intuition behind theme customization.

Let’s say we want the tick labels on the x-axis to appear larger. If

we’re using RStudio, we can type "axi" inside the

theme() function to explore available options via

autocomplete. Doing this reveals that the correct argument is

axis.text.x.

This tells ggplot2 that we want to change the text

labels on the x-axis. To specify how we want to change them, such as

adjusting the size or color, we use the

element_text() function. For example, here’s how we

would increase the text size for the x-axis in our original scatter

plot:

# Change the size of text on the x-axis

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Age, y = Fare)) +

geom_point() +

theme_light() +

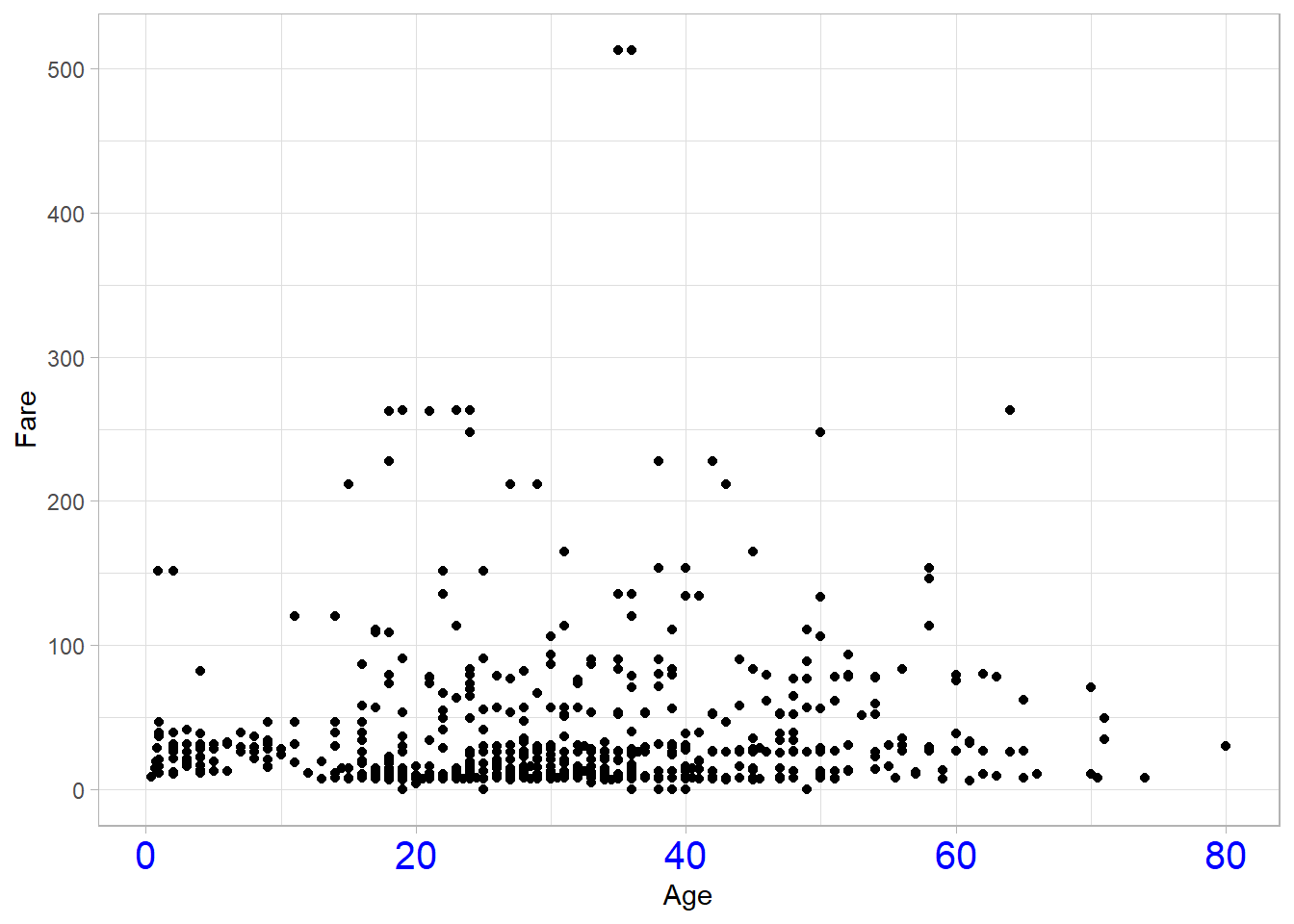

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(size = 15))

As a result, the x-axis labels now appear larger. We can clearly see this when comparing them with the unchanged y-axis labels. We can also modify other attributes, such as color. In the example below, the x-axis labels are now both larger and blue:

# Change the size and color of text on the x-axis

titanic_subset %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Age, y = Fare)) +

geom_point() +

theme_light() +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(size = 15, color = "blue"))

This example gives just a glimpse into the types of layout changes

you can make using theme(). It’s highly recommended to

experiment with these options and adjust your plots based on the

needs of your audience or the context of your analysis.

For more details, you can visit the official ggplot2 website to

explore theme documentation. Additionally, RStudio provides publicly

available

ggplot2 cheat sheets, which are a helpful reference when customizing your plots.

19.8 Recap

In this chapter, we explored key types of plots in

ggplot2, including bar plots, box plots, line plots,

and the use of facets to create multiple subplots based on

categorical variables. We also discussed how to customize the

appearance of plots through themes and how to control aesthetics

either globally within the ggplot() function or locally

within individual geoms. These tools form the foundation for

effective and flexible data visualization in R.